©Damen,

2021

Classical Drama

and Theatre

Return to Chapters

SECTION 1: THE ORIGINS OF WESTERN THEATRE

Chapter 3: The Early

Greek World, History and Prehistory

[For a more detailed history and cultural

overview of ancient Greece, see the Perseus web site (click

here).] |

I. Geography and Greek Culture

The

geography of Greece is a primary factor, if not the pre-eminent feature of the

culture and lives of the ancient populations who lived there. Inhabiting an

area that is ninety percent mountains with little arable land forced the Greeks

into ways of life that did not center strictly around farming and agriculture.

They were, for the most part, driven to go to sea to make ends meet. Indeed,

no place in Greece is further than fifty miles from the sea, so the inevitability

of fishing and maritime adventure was incumbent upon many in antiquity, as it

still is. To this day, many Greeks make a living in shipping, for instance,

Aristotle Onassis, the multi-millionaire who acquired a fortune in international

trade and married Jacqueline Kennedy after the assassination of her first husband.

The

geography of Greece is a primary factor, if not the pre-eminent feature of the

culture and lives of the ancient populations who lived there. Inhabiting an

area that is ninety percent mountains with little arable land forced the Greeks

into ways of life that did not center strictly around farming and agriculture.

They were, for the most part, driven to go to sea to make ends meet. Indeed,

no place in Greece is further than fifty miles from the sea, so the inevitability

of fishing and maritime adventure was incumbent upon many in antiquity, as it

still is. To this day, many Greeks make a living in shipping, for instance,

Aristotle Onassis, the multi-millionaire who acquired a fortune in international

trade and married Jacqueline Kennedy after the assassination of her first husband.

Ironically, while the mountainous topography pushed the Greeks to explore lands

far beyond their immediate locale, at the same time it also separated the cities

of Greece and obstructed intra-Hellenic contact, leading many of them to develop

along discrete, sometimes incompatible lines. For instance, settlements as close

as Athens and Thebes, which are less than sixty miles apart, not only came to

see each other as "foreign" but even evolved a long-lasting rivalry

that persisted into the Classical Age. Ironically, in some ways the ancient

Greeks became generally friendlier with peoples across the sea than their own

neighbors because the landscape made foreign nations seem "closer"

than many cities on the Greek mainland.

Overall, their geographical situation forced the ancient Greeks from early

on to look outward from their immediate locality and internationalize their

interests. This broadened their horizons and exposed them like few other civilizations

to foreign ideas and ways of living. The ensuing cosmopolitanism played an important

role in their development as a focal group in ancient Western Civilization.

For a people living on the edge of nowhere, they found themselves uniquely thrust

in medias res ("into the middle of things").

II. The Prehistory of Greece

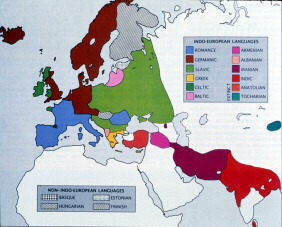

The earliest inhabitants of Greece are a mysterious—and possibly mythological—people

called the Pelasgians about whom we know very little. These

natives and their culture were overwhelmed and ultimately utterly annihilated

by the invasion of a new people known now as the Indo-Europeans

(click here to read more

about the Indo-Europeans). If it were not for a handful of Pelasgian words like

plinth ("brick"), a term preserved in ancient Greek, along

with a few city-names like Corinth and other scattered vestiges of the Pelasgians'

language, we would hardly even know these people ever existed. That's how completely

devastating was the Indo-European conquest of this region.

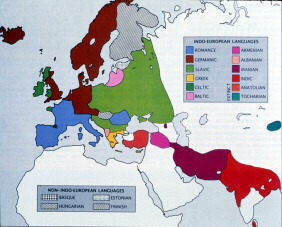

So,

when people today study the ancient Greeks, they are examining not the earliest

known humans in the area but later invaders called the Indo-Europeans. This

is clear because of the language the Greeks spoke. All extant forms of ancient

Greek clearly derive from a common ancestor called Proto-Indo-European,

a language that engendered a large number of daughter languages found across

much of the Eurasian continent, all the way from India to Norway. These closely

related tongues show that the Indo-Europeans must have migrated over thousands of miles in different directions, displacing natives and settling themselves

in lands across a wide swath of the Eurasian continent.

So,

when people today study the ancient Greeks, they are examining not the earliest

known humans in the area but later invaders called the Indo-Europeans. This

is clear because of the language the Greeks spoke. All extant forms of ancient

Greek clearly derive from a common ancestor called Proto-Indo-European,

a language that engendered a large number of daughter languages found across

much of the Eurasian continent, all the way from India to Norway. These closely

related tongues show that the Indo-Europeans must have migrated over thousands of miles in different directions, displacing natives and settling themselves

in lands across a wide swath of the Eurasian continent.

Another thing we know about the Indo-Europeans is that they tended to enter

a region in successive waves. That is, Indo-Europeans rarely migrated into an

area just once, and Greece was no exception. As early as 2000 BCE one Indo-European

contingent had begun infiltrating the Greek peninsula and by the end of that

millennium at least three major discrete migrations of these intruders had surged

across various parts of Greece.

One

racial group of these Indo-Europeans was called the Ionians.

They settled along the eastern coast of Greece, in particular the city of Athens,

and along the western coast of Asia Minor (modern Turkey).

Another group, the Dorians, settled the Peloponnese

(the southern part of Greece) and many inland areas. The result was a "dark

age" accompanied by massive disruptions in the Greek economy and civilization,

including a total loss of literacy.

One

racial group of these Indo-Europeans was called the Ionians.

They settled along the eastern coast of Greece, in particular the city of Athens,

and along the western coast of Asia Minor (modern Turkey).

Another group, the Dorians, settled the Peloponnese

(the southern part of Greece) and many inland areas. The result was a "dark

age" accompanied by massive disruptions in the Greek economy and civilization,

including a total loss of literacy.

This dark age lasted about three centuries, from 1100 to 800 BCE and, while

it seems from our perspective today like a dismal time, it must have been a

dynamic and fascinating period in Greek history, perhaps a wonderful time to

have lived. The lack of written historical records—the inevitable product

of the age's illiteracy—leaves the impression of a vast void but, to judge

the period from its outcome, it gave shape to much of the rest of Greek history.

Many of the things we associate with Greek culture—for instance, vase-painting,

epic poetry, and ship-building—assumed their basic and most familiar forms

during this "dark" age.

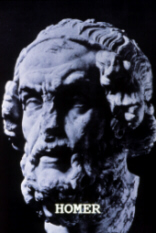

Particularly,

many of the Greek myths read and studied today are traceable to this time period.

Quite a few are set in the generations just before the dark age or in its early

phases. For example, the famous cycle ("collection") of myths about

the Trojan War—if, in fact, it is based on any real event

in history—must date to some time around 1185 BCE. These myths found their

most brilliant expression in the early Greek epic poems attributed

to Homer, ancient Greece's greatest pre-classical poet.

Particularly,

many of the Greek myths read and studied today are traceable to this time period.

Quite a few are set in the generations just before the dark age or in its early

phases. For example, the famous cycle ("collection") of myths about

the Trojan War—if, in fact, it is based on any real event

in history—must date to some time around 1185 BCE. These myths found their

most brilliant expression in the early Greek epic poems attributed

to Homer, ancient Greece's greatest pre-classical poet.

Homer's

first epic, The Iliad, tells the tale of the Greeks'

sack of Troy and the anger of their formidable hero, Achilles. Among other famous

characters included there are the beautiful Helen and her hapless Greek husband

Menelaus, the king of Sparta. His brother, Agamemnon, the king of neighboring

Mycenae who leads the expedition of Greeks to Troy, is married to Helen's sister

Clytemnestra with whom he has several children including Electra and Orestes.

All later became important characters in drama as well as epic. The gods also

play a large role in The Iliad, in particular, the king of the gods

Zeus, the sun god Apollo, and the goddess of wisdom Athena.

Homer's

first epic, The Iliad, tells the tale of the Greeks'

sack of Troy and the anger of their formidable hero, Achilles. Among other famous

characters included there are the beautiful Helen and her hapless Greek husband

Menelaus, the king of Sparta. His brother, Agamemnon, the king of neighboring

Mycenae who leads the expedition of Greeks to Troy, is married to Helen's sister

Clytemnestra with whom he has several children including Electra and Orestes.

All later became important characters in drama as well as epic. The gods also

play a large role in The Iliad, in particular, the king of the gods

Zeus, the sun god Apollo, and the goddess of wisdom Athena.

Homer's

other epic, The Odyssey, narrates the adventures of the Greek hero

Odysseus as he wanders around the Mediterranean Sea trying for ten years to

get home to Ithaca, an island on the western coast of Greece. Along the way

he encounters a number of deities and monsters and is involved in much mayhem. Ultimately

with the help of his patroness, the goddess Athena, he arrives back in his kingdom

safe, if not entirely sound. There he encounters his wife Penelope and son Telemachus

after an absence of twenty years.

Homer's

other epic, The Odyssey, narrates the adventures of the Greek hero

Odysseus as he wanders around the Mediterranean Sea trying for ten years to

get home to Ithaca, an island on the western coast of Greece. Along the way

he encounters a number of deities and monsters and is involved in much mayhem. Ultimately

with the help of his patroness, the goddess Athena, he arrives back in his kingdom

safe, if not entirely sound. There he encounters his wife Penelope and son Telemachus

after an absence of twenty years.

These stories convey such a compelling sense of realism about their day and

time that more than one scholar has been tempted to see in them history rather

than mere myth, but their historicity is questionable at best. One such investigator

was Heinrich Schliemann, a nineteenth-century German millionaire

and archaeologist, who excavated the site that is now known as Troy.

This ancient settlement in the northwestern corner of Asia Minor near the straits that separate

Asia and Europe indeed contains the ruins of a once-great city that thrived

in the middle to late second millennium BCE, but is this site Homer's Troy? Moreover, even if its name was Troy—and there is no firm evidence to that effect—that

still leaves open the question of the extent to which Homer's epics preserve

historical reality. The debate about the amount of verifiable history preserved

in Homeric epic lingers unresolved to this day, a tribute to the enduring, gripping

picture of humanity painted by this purportedly blind poet. [To read more about

Troy, Homer and Schliemann, click here.]

III. The Pre-Classical Age of Greek History

With

the reappearance of written records after the dark age, Greek history as such

comes back into focus. From the earliest extant inscriptions and vase-paintings

with writing on them, we know that the alphabet was introduced to the Greek

world at some point around 800 BCE, which is probably at or about the time Homer

himself lived. This provides one way to explain why his epics, originally composed

"orally" (i.e. as narratives that were not written down), were preserved.

They came into being at just the right moment, when oral poets were still active but writing had been introduced so oral poetry could be recorded. This revolutionary

period in Greek history—and indeed world history—witnessed the rise

of the polis, the classical city-state (for instance,

Athens, Sparta and Corinth) which would dominate the political scene for several

centuries. These quasi-independent communities in their inter-political rivalry

elevated Western civilization to unprecedented heights.

With

the reappearance of written records after the dark age, Greek history as such

comes back into focus. From the earliest extant inscriptions and vase-paintings

with writing on them, we know that the alphabet was introduced to the Greek

world at some point around 800 BCE, which is probably at or about the time Homer

himself lived. This provides one way to explain why his epics, originally composed

"orally" (i.e. as narratives that were not written down), were preserved.

They came into being at just the right moment, when oral poets were still active but writing had been introduced so oral poetry could be recorded. This revolutionary

period in Greek history—and indeed world history—witnessed the rise

of the polis, the classical city-state (for instance,

Athens, Sparta and Corinth) which would dominate the political scene for several

centuries. These quasi-independent communities in their inter-political rivalry

elevated Western civilization to unprecedented heights.

This epoch now known as the Pre-Classical Age (800-500 BCE)

is also called the Age of Tyrants because powerful individuals

came to rule the majority of these city-states by overthrowing the existing

regime in a military coup. While our word "tyrant" which comes from

the Greek tyrannos has strongly negative overtones,

the Greek term had in antiquity both negative and neutral connotations, or sometimes

even positive ones. That is, not all Greek tyrannoi (plural of tyrannos)

were seen as "tyrannical."

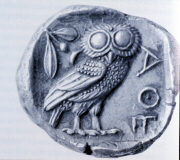

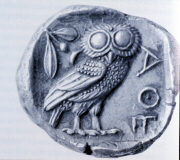

One,

in particular, Pisistratus of Athens, was a visionary who did

much good for his city. He established festivals that united the Athenians culturally,

boosted their economy by creating a market for Athenian exports and stabilized

Attic (i.e. Athenian) coinage, making it widely respected throughout

the Mediterranean world. Though he brought himself to power through force and

violence, he used the position he assumed to better the lives of his fellow

townsmen in general. He remained in power for many years and, when he died in

the early 520's BCE, his sons inherited his power. While they did not manage

Athens as well as their father had and were eventually ousted, Pisistratus'

lasting contributions laid the groundwork for the Athenians' rise to prominence

in the next century, the fifth century BCE (500-400 BCE), the Classical

Age.

One,

in particular, Pisistratus of Athens, was a visionary who did

much good for his city. He established festivals that united the Athenians culturally,

boosted their economy by creating a market for Athenian exports and stabilized

Attic (i.e. Athenian) coinage, making it widely respected throughout

the Mediterranean world. Though he brought himself to power through force and

violence, he used the position he assumed to better the lives of his fellow

townsmen in general. He remained in power for many years and, when he died in

the early 520's BCE, his sons inherited his power. While they did not manage

Athens as well as their father had and were eventually ousted, Pisistratus'

lasting contributions laid the groundwork for the Athenians' rise to prominence

in the next century, the fifth century BCE (500-400 BCE), the Classical

Age.

Other

tyrants around the Greek-speaking world did much the same. More than one is

famous as a "lawgiver," the man who, even while sole ruler, paved

the way for fair and representative government in his city. Thus, this age is

also known as the Age of Lawgivers. The introduction of writing,

no doubt, played a great role in the advancement of law. Initially law codes, no doubt, entailed

little more than the codification of already existing custom—in Greek,

the word for "custom" is nomos which eventually became the

term used for "law"—in deed, Athens had no less than two (in)famous lawgivers:

Draco at the end of the seventh century (600's) BCE and Solon

in the next generation (the early part of the sixth century, ca. 580 BCE). Both

have left their imprint on English. A solon today means a "politician,"

and draconian means "extremely harsh or punitive" because

Draco was famous for the severity of the punishments his laws imposed.

Other

tyrants around the Greek-speaking world did much the same. More than one is

famous as a "lawgiver," the man who, even while sole ruler, paved

the way for fair and representative government in his city. Thus, this age is

also known as the Age of Lawgivers. The introduction of writing,

no doubt, played a great role in the advancement of law. Initially law codes, no doubt, entailed

little more than the codification of already existing custom—in Greek,

the word for "custom" is nomos which eventually became the

term used for "law"—in deed, Athens had no less than two (in)famous lawgivers:

Draco at the end of the seventh century (600's) BCE and Solon

in the next generation (the early part of the sixth century, ca. 580 BCE). Both

have left their imprint on English. A solon today means a "politician,"

and draconian means "extremely harsh or punitive" because

Draco was famous for the severity of the punishments his laws imposed.

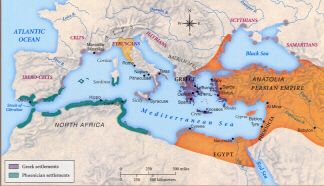

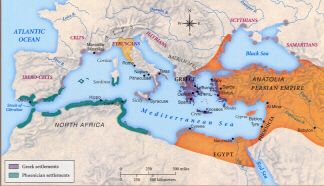

Also,

because at this time the Greeks began to colonize large parts of the Mediterranean

world—in particular, Asia Minor and Sicily (the large

island southwest of Italy)—and the coastal regions of the Black

Sea as well, this age has also been dubbed the Age of Colonization.

In particular, the Greeks settled in large numbers in southern Italy which came

to contain so many of them that the later Romans referred to the area as Magna

Graecia ("Big Greece"). In part because of their essentially

Greek heritage, the people and culture of southern Italy and Sicily are to this

day quite different from those of central and northern Italy.

Also,

because at this time the Greeks began to colonize large parts of the Mediterranean

world—in particular, Asia Minor and Sicily (the large

island southwest of Italy)—and the coastal regions of the Black

Sea as well, this age has also been dubbed the Age of Colonization.

In particular, the Greeks settled in large numbers in southern Italy which came

to contain so many of them that the later Romans referred to the area as Magna

Graecia ("Big Greece"). In part because of their essentially

Greek heritage, the people and culture of southern Italy and Sicily are to this

day quite different from those of central and northern Italy.

The reason Greek colonization occurred on such a grand scale at this time goes

back to changes in Mesopotamia (the modern Middle East), more than once the

distant impetus for significant developments in the Western world. In the eighth

century BCE, the Assyrians had come to dominate most of the ancient Near East.

Their conquest and brutal treatment of captive states demolished many of the

existing social, political and economic structures in the day.

Among those subjugated to the Assyrians were the Phoenicians

who lived on the eastern seaboard of the Mediterranean. From that crossroad,

they had enriched themselves through a network of commercial exchange protected

by a powerful navy but, when the Assyrians conquered and uprooted them, that

navy evaporated and the trade routes of the eastern Mediterranean were opened

up. The Greeks stepped into the vacuum, making a new life of wealth for themselves

in shipping and cultural exchange. They then went on to colonize those areas where

they traveled most often, in part to protect their trade routes. Put simply,

had the Assyrians not shattered the Phoenicians, the Greeks might never have

found the economic room and energy needed to spark the cultural revolution they undertook

in the Classical Age.

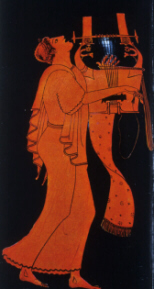

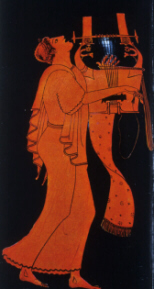

Yet

one more way to refer to this period is the Lyric Age, a name

derived the dominant form of literature in the day. While long heroic epics

predominated as the principal form of narrative entertainment in earlier days,

by the middle of pre-classical times (ca. 650 BCE) a new kind of poetry had begun

to spread across the Greek world. These poems were shorter, livelier, and focused

on modern life and love, not the redoubtable feats of a glorious past. Because the singers of these

poems often accompanied themselves on the lyre—the lyre

is a stringed musical instrument that could be plucked to create certain harmonies—this

sort of poetry came to be known as lyric poetry.

Yet

one more way to refer to this period is the Lyric Age, a name

derived the dominant form of literature in the day. While long heroic epics

predominated as the principal form of narrative entertainment in earlier days,

by the middle of pre-classical times (ca. 650 BCE) a new kind of poetry had begun

to spread across the Greek world. These poems were shorter, livelier, and focused

on modern life and love, not the redoubtable feats of a glorious past. Because the singers of these

poems often accompanied themselves on the lyre—the lyre

is a stringed musical instrument that could be plucked to create certain harmonies—this

sort of poetry came to be known as lyric poetry.

By

600 BCE lyric poetry ruled the ancient Greek entertainment scene. Lyric poets

and their musical verse were in great demand with the public, much the way rock

stars are today. Indeed, the analogy of lyric poetry and rock music is not altogether

off-base. In their day, Greek lyric poets were idolized, imitated and at least

one is reported to have performed in a state of intoxication.

By

600 BCE lyric poetry ruled the ancient Greek entertainment scene. Lyric poets

and their musical verse were in great demand with the public, much the way rock

stars are today. Indeed, the analogy of lyric poetry and rock music is not altogether

off-base. In their day, Greek lyric poets were idolized, imitated and at least

one is reported to have performed in a state of intoxication.

The most famous of these, however, is also one of the

few woman's voices we hear from any quarter of antiquity. Her name is Sappho,

and her love poetry is perhaps the most famous of all time. The beauty of Sappho's

lyrics in Greek was heralded throughout antiquity, as was the complexity, subtlety

and rapturous grace of her rhythms and melodies.

Unfortunately, most of her poetry is now lost, shattered in its long passage

through neglectful ages. So much has been disappeared that we are not sure we have even a single

poem of hers complete. But the many fragments of her songs which survive today

attest to the high reputation in which the ancients held her. More important

for our purposes, lyric poetry like Sappho's played an important role in the

formulation of Greek drama which borrowed heavily from lyric modes of expression

and, in fact, rose at the very time that lyric poetry began to decline. So, Sappho's

legacy lived on, at least in part, through the tragedies and comedies that followed in her wake.

In the end, be it called the Lyric Age, the Age of Colonization, the Age of

Tyrants, the Age of Lawgivers or simply the Pre-Classical Age, these three centuries

of Greek civilization (800-500 BCE) are by any name one of the great revolutionary

periods in human history. Were it not followed by an age even more magnificent

(i.e. the Classical Age), this could easily be deemed a golden age. If nothing

else, all the titles of this epoch point up the centrality of these

centuries as a pivotal and formative moment in not only Greek history but all

of Western Civilization. And so it will come as little surprise that this was

the time and place, the laboratory if you will, where Greek drama was created.

Terms, Places, People and Things to Know

|

Pelasgians [puh-LASS-gee-uns]

Indo-Europeans

Proto-Indo-European

Ionians [eye-OWN-nee-uns]

Athens

Asia Minor

Dorians

Peloponnese [PELL-oh-pun-NEESE]

Trojan War

Epic

Homer

The Iliad

Heinrich Schliemann [SCHLEE-man]

Troy

Polis [PALL-liss]

Pre-Classical Age

|

Age of Tyrants

Tyrannos [TURR-raw-noss]

Pisistratus of Athens [pie-SISS-trah-tuss]

Attic

Classical Age

Age of Lawgivers

Solon [SAW-lahn]

Sicily

Black Sea

Age of Colonization

Magna Graecia [GRY-kee-yuh]

Phoenicians [FONE-nee-shuns]

Lyric Age

Lyre

Lyric Poetry

Sappho [SAFF-foe] |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The

geography of Greece is a primary factor, if not the pre-eminent feature of the

culture and lives of the ancient populations who lived there. Inhabiting an

area that is ninety percent mountains with little arable land forced the Greeks

into ways of life that did not center strictly around farming and agriculture.

They were, for the most part, driven to go to sea to make ends meet. Indeed,

no place in Greece is further than fifty miles from the sea, so the inevitability

of fishing and maritime adventure was incumbent upon many in antiquity, as it

still is. To this day, many Greeks make a living in shipping, for instance,

Aristotle Onassis, the multi-millionaire who acquired a fortune in international

trade and married Jacqueline Kennedy after the assassination of her first husband.

The

geography of Greece is a primary factor, if not the pre-eminent feature of the

culture and lives of the ancient populations who lived there. Inhabiting an

area that is ninety percent mountains with little arable land forced the Greeks

into ways of life that did not center strictly around farming and agriculture.

They were, for the most part, driven to go to sea to make ends meet. Indeed,

no place in Greece is further than fifty miles from the sea, so the inevitability

of fishing and maritime adventure was incumbent upon many in antiquity, as it

still is. To this day, many Greeks make a living in shipping, for instance,

Aristotle Onassis, the multi-millionaire who acquired a fortune in international

trade and married Jacqueline Kennedy after the assassination of her first husband.