©Damen,

2021

Classical Drama

and Theatre

Return to Chapters

SECTION 3: ANCIENT GREEK COMEDY

Chapter 9: Aristophanes

I. Aristophanes'

Life and Work

Whether he deserved it or not, Aristophanes has emerged as

the only exponent of Old Comedy who has any works surviving intact. Out of a total corpus of forty or more, eleven of his comedies have been preserved through a manuscript

tradition. Equally important, these plays date from 425 to 388 BCE, constituting

a sampling of all major phases of his playwriting career. Though time-bound

in their subject, his dramas are still widely produced because their themes

speak to issues of war, sex, poetry, government, among other timeless concerns.

A. Aristophanes' Life and Career

Aristophanes was born into a good Athenian family at some point around the 450's BCE and died around 386 BCE. Thus, at a relatively young age he began

to flourish—comic genius of the sort he shares with Menander, Shakespeare,

Molière and Wilde tends to flower early—but unlike so many others

of his ilk whose brilliance all too often fizzles out early, his light burned

bright until late in life. Such a prolonged career requires dramatic transformations

of a playwright, as the world changes around him, and Aristophanes, as few others

have, reinvented himself several times through his career.

The most significant transition he undertook came after the Peloponnesian War

when comedy could no longer directly satirize celebrities or politicians and

the Athenians stopped investing large sums on ludicrously elaborate choruses.

Aristophanes, by then in his fifties, abandoned the complex choral songs that had been a hallmark of his style up until then and, even more of a surprise,

generalized the subjects of his abuse, even though he had attacked individuals

throughout his early career, even constructing whole comedies around the foibles

of one well-known personality. The reason he made so great a change as this

is clear: he loved the theatre and, by forcing himself to evolve in ways he,

no doubt, would rather not have, he not only maintained his presence on the

Athenian stage but also cleared the ground for a new type of comic drama, the New

Comedy that would dominate Greek theatre in the next age.

B. The Nature and Significance of Aristophanes' Comedy

As far as some are concerned today, Aristophanes'

plays—and indeed Old Comedy in general—seem to present a startling

paradox, in which exquisitely beautiful choral odes mingle happily with startlingly

earthy jests about sex and other bodily functions. To wit, many in Victorian

England were fascinated with Aristophanes' gift for lyric poetry, his wit and

sagacity, but at the same time his scatological humor appalled them, so much

so that their texts of Aristophanes edit out many passages in his plays. While few

today are so squeamish about off-color jokes, even modern audiences are sometimes

left breathless by Aristophanes' explicit references to eros and digestion

(note).

Because Aristophanes mentions many political figures

and attitudes popular in his day, later ages valued him as a source of historical

information as much as a humorist and dramatist. That, along with his use of

interesting idioms and jargon peculiar to the Classical Age, comprises, no doubt,

the main reason so many of Aristophanes' plays have survived to our time, when

more respected—and respectable—playwrights, such as Sophocles, are

less well attested in the tradition of western literature. As witness to the

sort of interest he attracted in later ages, there still exist scholia

for his plays, that is, notes written in later antiquity by scholiasts,

researchers who produced commentaries on the texts of ancient literature. Scholiastic commentaries

on Aristophanes were composed to explain his plays to ancient readers who, living

after Aristophanes' day, would not have understood his political references

or other comments on current events in his day any more than readers untrained

in classical history would today.

Thus, for theatre historians the scholia are

immeasurably valuable because they include data about the production of ancient

plays, such as the dates, festivals, and actors of a play's premiere. What is

more, the Aristophanes scholia situate all his surviving plays in specific years,

so we can follow his career better than that of any other ancient Greek playwright

(note). As a result, Aristophanes' plays

have come to be important not just to theatre historians, but to all

ancient historians because, for instance, his awareness or ignorance of a certain

event in a play written in a specific year can be crucial in determining the

chronology of important affairs during his lifetime. Next to Thucydides, the

great historian of the Classical Age, Aristophanes is the best contemporary

source we have for Athenian history in the later fifth century BCE, the period

of the Peloponnesian War.

In regard to Aristophanes' drama itself, much

less is certain. It is impossible, for instance, to say for certain whether

Aristophanes' plays were ever restaged after their first production, either during his lifetime or

in the post-Classical Age.

While their topicality argues against their long-term viability in the ancient

theatre—political jokes tend to lose currency very quickly—other

evidence suggests certain plays may have been revived in performance or were

at least circulated in published form (note).

But cultural immediacy is not the only issue at hand here—nor is it necessarily

the most compelling either—since the themes of Aristophanes' plays, such as

the power of sex, modern art, and the corruption of the legal system, give his

plays universal appeal now, so why not back in antiquity, too? It is hard to believe these

masterpieces of comic fantasy did not find eager viewers in post-classical antiquity, just as they do so often today, theatre-goers to whom they appealed long after the

immediate society and time for which they were written had passed. Too bad there's

no unequivocal evidence to that effect.

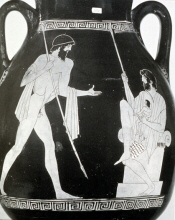

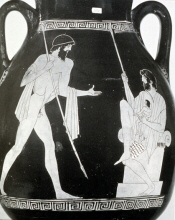

One modern scholar has, however, suggested

that a series of vases from southern Italy, which were once construed as evidence

of early native comedy on the Italian peninsula, are, in fact, representations

of Aristophanic drama and other Old Comedies. He posits; they were exported

from Athens to the Greek-speaking population living south of Rome in the fourth

century BCE, which is not an unreasonable supposition, but it would be nice to

have more data underlying a thesis of such weight (note).

All in all, these vases may constitute some measure of evidence that Aristophanes'

drama did, in fact, reach a wider range of viewers than his immediate Athenian contemporaries,

and if they did, it would be little surprise to anyone who's seen Aristophanes

on stage.

II. Aristophanes' Early Plays (427-421 BCE)

A. Aristophanes' First Two Plays (427-426 BCE)

1. The Banqueters

Given all this, we can trace the history of Aristophanes' evolution as a comic

poet as we can no other dramatist from the Classical Age. This applies not only

to those plays surviving but also ones now lost. For example, Aristophanes wrote

The Banqueters (427 BCE), his first play—by

contrast, we don't know the titles of the first plays produced by any of the

tragedians in the Classical Age—when he was still too young to produce

at the Dionysia under his own name. So one Callistratus, an otherwise unknown

older associate of Aristophanes, produced the play, though it is clear the public

knew who the real author was and accepted the ruse because in the parabasis

of a later play (The Clouds) Aristophanes says:

I still remember that glorious day when the judges—men

of extraordinary taste and discrimination, it is a joy to speak—awarded

the first prize to my youthful comedy, The Banqueters. Now at that

time, gentlemen, my Muse was the merest slip of a girl, a tender virgin who

could not—without outraging all propriety—give birth. So I exposed

her child, her maiden effort, and a stranger rescued the foundling.

That he also won first prize with his first venture in comedy is a notable

achievement, bespeaking Aristophanes' native talent for comic drama. The teen-pregnancy

joke, however, is also notable in that it hints at the plot of many a Greek comedy to

come.

The Banqueters is telling in other ways as well. For instance, its name is,

in fact, a good way for a young Athenian playwright to begin his career since,

at least to judge from komoidia

("party-song"), banqueting had deep roots in Greek comedy. The surviving

fragments of The Banqueters show that it featured a chorus of feasters,

as well as an agon between a good and a profligate young man, a scenario which

looks ahead to The Clouds where Just Reason and Unjust Reason dispute, with

the soul of a young man at stake. From a play that is both forward-looking and

steeped in the tradition of Greek comedy, it seems safe to conclude that the

young Aristophanes had a clear understanding of the history of the genre upon

which he was embarking.

2. The Babylonians

The next year (426 BCE) Aristophanes competed at the Dionysia again with another

comedy, The Babylonians. Like The Banqueters,

this play is no longer extant, and unfortunately we know relatively little about

it other than that it featured the god Dionysus as a character. About its reception,

however, we are much better informed since we are told that Aristophanes in The

Babylonians viciously satirized current politicians, particularly the reigning

demagogue Cleon. In retaliation for criticizing him in front

of Athenians and foreigners alike—recall that important

foreigners attended the Dionysia—Cleon prosecuted Aristophanes on

the charge of unpatriotic behavior. In the course of this lawsuit, he also

attacked the good name of Aristophanes' family and thus Aristophanes' right

to produce plays at all, a competition in those days restricted to native Athenians.

We do not know the outcome of the case, but apparently Cleon's charge did not

hold up in court since Aristophanes was able to stage comedies at either the Dionysia or Lenaea every year henceforth,

until at least 421 BCE. The only perceptible

impact of Cleon's case was that in the following year (425 BCE) Aristophanes'

next comedy, The Acharnians, was presented not at the Dionysia but

the Lenaea, a festival where foreigners were

not in attendance. So, Cleon seems to have won at least a partial victory

inasmuch as he restricted Aristophanes' vicious satire of him to an Athenians-only

audience, which was probably what the demagogue really wanted anyway.

B.

Aristophanes' Surviving Plays from 425-421 BCE

1. The Acharnians

The Acharnians, the earliest surviving play by Aristophanes,

features a hero who is an average man fancifully named Dicaeopolis ("Just-City").

In the course of the play, this prototypical comic commoner, tired of the ravages

of war, makes a separate, personal peace treaty with the Spartans. The plot

of this comedy is unnoteworthy except that it ends in a riotous, licentious

revel evidently intended to induce the Athenians into signing a treaty with

the Spartans by reminding them of all the sensual pleasures concomitant with

peace.

This play cannot have pleased Cleon any more than The Babylonians.

It includes several jabs at the demagogue who generally advocated that the Athenians

maintain an aggressive posture against the Spartans in the war. In spite of

any displeasure Cleon may have felt or expressed, Aristophanes' play won its

playwright another first prize, though this time at the Lenaea, the less illustrious

of the dramatic festivals. Still, the young Aristophanes was already a two-time

winner in just his first three outings—perhaps even a three-time

winner since there's no record about how The Babylonians fared—whatever

the count, it's an impressive record for a newcomer.

2. The Knights

By the next year (424 BCE) Cleon had reached the height of his political power

and influence, in large part because he had managed to capture and imprison

a number of important Spartans, a serious and demoralizing blow to the Athenians'

enemies. Given the height of his political power and his personal outrage at

the young playwright's taunts, one might have expected Aristophanes to let up

the barrage of comic barbs he aimed at the demagogue. But that would be to underestimate

several factors at hand: the force of Aristophanes' genius, his youth, his idealism

and the innate liberality of Athenian democracy.

Contrary to common sense, then, in 424 BCE Aristophanes

produced The Knights, his most stinging attack yet

on Cleon, though the play was again restricted to the Lenaea. And while the

young dramatist may have been bold enough to make a third direct assault on

the reigning leader of Athens, others apparently were not. For one, the producer

Callistratus refused to work with Aristophanes this time, as he had before on

The Banqueters. Fortunately, the playwright was now old enough to stage

a play under his own name, but then several actors also panicked and left the

show. None, it seems, had the audacity to ridicule the powerful Cleon so blatantly.

That left Aristophanes with little choice but to perform in his own play—a

thing unheard of in Greek drama since the days of Aeschylus—and take

the role of the comic villain who, though not named Cleon as such, was a thinly

disguised caricature of the politician called "the Paphlagonian" (note).

Finally, to make matters even worse, mask-makers refused to create a comic likeness

of Cleon so Aristophanes had to play the part without a mask. In brash contempt

of his peers in theatre and the compulsion of political correctness, Aristophanes

went on stage, his face smeared with wine lees to make it resemble his vision

of the purple, bloated cheeks of the hot-tempered rabble-rouser, a bold challenge

to Cleon to sue him a second time.

Unlike so much political satire, The Knights is actually very clever,

funny even today. It's also anything but subtle. The Paphlagonian is the servant

of another character called Demos ("People"), a collective representation

of the Athenians as a crude, fat, boorish, self-indulgent, superstitious, weak-minded,

rich householder. This dissolute and easily distracted moron has had a series

of fawning servants, the latest of whom is the "wily" Paphlagonian.

But of all Demos' scoundrelly servants, the Paphlagonian outdoes the lot, especially

in lying, cheating and pilfering. Through fawning and obsequious behavior he

has won Demos' heart, but to the servants under him the Paphlagonian is surly

and insolent.

In the course of the play, these inferiors turn on the Paphlagonian and urge

another man, a lowly sausage-seller, to try to win Demos' heart from the newcomer.

The sausage-seller and the Paphlagonian hold a contest to see who can out-flatter,

out-boast, and out-cater-to-the-baser-tastes-of Demos. As this is a comedy, naturally

the sausage-seller wins by out-Cleoning the Paphlagonian. Concluding, then,

with the suggestion that a hotdog vendor would make a better leader of Athens

than the current powers that be, the play ends happily as the Paphlagonian is

ousted from Demos' house, a blunt parable for removing Cleon from power.

And from this Aristophanes once again won first prize, his third—perhaps

his fourth—at such a young age. Of course, as

Aristotle notes, people tend not to take comedy seriously, so nothing came

of Aristophanes' ridiculous but earnest attempt to make the Athenians see Cleon

for the dangerous demagogue he really was. In fact, Cleon solidified his control

all the more over the Athenians after 424 BCE. Nor is there any record that

he prosecuted Aristophanes for writing The Knights. Perhaps he had

learned what many public figures eventually come to recognize: all publicity,

good or bad, is good.

3. The Clouds

In 423 BCE, Aristophanes finally turned from politics and Cleon-bashing to

a very different tack on life in the day and won himself a slot in the Dionysia

for the first time in several years. In The Clouds

he attacked philosophy and the sophists

who had by then been challenging the Athenians' traditional modes of thinking

for some time. Rather unfairly, he made the native-born Athenian philosopher

Socrates the target of his comic onslaught, setting him up

as the champion of the crack-pot ideas that were circulating among the intellectual

avant-garde at the time and threatening to undermine the moral order of Athens

and corrupt its youth.

Aristophanes must have known that Socrates was not one of the sophists

responsible for the crimes he accuses him of. Men like Protagoras, a veritable sophist who did indeed advocate the sort

of relativism that claimed good and bad are negotiable values, would have been

far fairer prey. To look at the situation from the perspective of a comic

poet, however, reveals the real reasons Socrates was chosen for abuse. For one thing,

Protagoras and many of his ilk were foreigners, whereas Socrates was a well-known,

local figure who was clearly associated with the sophists, even if he professed

not to agree with them.

For another—and this is much more important for a comic poet and social

satirist like Aristophanes than any actual principle of philosophy—Socrates

was not what anyone would call handsome, which made him a ready target for physical

comedy. An anecdote handed down to us from antiquity claims that, when the actor

playing Socrates in The Clouds first entered the stage wearing a mask

that had been specially made to resemble the philosopher's infamous face, Socrates

was in the audience and stood up so the audience could have a better chance

to compare the mask with the real thing. Whatever his reason—perhaps a

tribute to the mask-maker, perhaps a way of saying, "I'll go along with

your joke, Aristophanes!," or perhaps a recognition like Cleon's that all

publicity is inherently good—Socrates' action is typical of the good-humored,

powerfully intelligent "father of Western philosophy."

The plot of The Clouds revolves around a father named Strepsiades

("Twister") who wants his son to be educated in the latest fashion,

so that the boy can win lawsuits for their family and make them all rich. So

Strepsiades enrolls his son in a fictitious school imagined to be run by Socrates, the ingeniously monikered Phontisterion ("The Thought-ery" or "The

Thought-Factory"). The rest of the play progresses through a series of

jokes at Socrates' and the sophists' expense, many of which are quite humorous

but, like the political jokes in The Knights, often independent of

plot development. In the end, the boy is trained in all sorts of subtle verbal

gimmickry, so that he can argue in favor of any case he wants, be it just or

not. And what he ultimately argues for is a son's fundamental right to beat

his father. At the end of the play he puts theory into action, but when he proceeds

to threaten his mother with a beating, too, the battered and indignant Strepsiades

burns down the Phontisterion.

Needless to say, such an ending would have pushed the technical limits of the

ancient Greek theatre to the edge and beyond. It makes sense, then, as the scholia

note, that this version of the ending of The Clouds, the one handed down to us in our manuscripts of the play, is a later revision

and not the one originally performed on stage in 423 BCE. This says two important

things about classical drama. First, a fifth-century comic playwright could

revise his work after its premiere, which begs the question of why and for whom—a

reading public? a subsequent production? and if so, where and when?—at

the same time, however, this evidence hints at the wider distribution of Greek

drama in the day, offering the tantalizing possibility that plays were not just

seen but also read as early as the Classical Age.

Second, the revised ending

accords well with another bit of information we know about The Clouds,

that this comedy was a "flop," as far as we know, Aristophanes' first

ever. Not only did it fail to win the Dionysia that year, but it was given the

last prize. As it turns out, one important factor in this play's failure had

nothing to do with the work itself but was simply an unfortunate coincidence

of timing. At the same festival, Aristophanes'

older rival Cratinus produced what would prove to be his last great comic

masterpiece, Pytine ("The Flask") (note).

Still, the loss must have stung Aristophanes badly—first wounds always

hurt the most!—so it is also possible to conclude that years later, with

this ignominious fiasco still sticking in his craw, he revised The Clouds,

even when there was no clear opportunity of restaging it. It was his way of closing the wound inflicted by his first significant failure on the stage, all

of which means we must proceed with some caution when looking to The Clouds

for indications about the performance of plays outside of the Dionysia and Lenaea

during the Classical Age. The text as we have it may not in every detail represent a script designed

to be staged, even if it comes from the hand of one of the most

productive and produced playwrights in western civilization.

4. The Wasps

In the following year (422 BCE) Aristophanes returned both to the Lenaea, where

he had already had two successes, and to the comic turf where he had been most

successful, the political arena. He produced a comedy called The

Wasps, a satire of the Athenian jury system. This play features

an old man who, since his son has become head of the house, has had much free

time on his hands. This old man named Philocleon ("Love Cleon") has

lately been spending his many leisure hours in court serving as a juror, becoming

virtually addicted to trials. As a consequence, his son named Bdelycleon ("Fart

Cleon") fears that the old man and his senile cronies will ruin Athens

by constantly voting according to their geriatric right-wing reactionary inclinations—read:

Cleon's political agenda—so Bdelycleon has locked his father Philocleon

in their house to prevent him from going to court and perpetuating Cleon's hate-mongering,

hawkish policies.

In the first scenes of the play, Philocleon tries to escape but is stopped

by Bdelycleon, who finally convinces the old man to stay home by staging a do-it-yourself,

home-style trial. To understand the main joke of this play, it is crucial to

understand current political events in Athens. An Athenian general named Laches

had recently been put on trial for embezzling tribute monies he was supposed

to be bringing home to Athens from Sicily. In court, Laches' lawyers had pleaded

that life at the front was terribly difficult and he needed the money to support

his family while he was away. They went so far as to bring Laches' family into

court where they wept and wailed in the background, begging for mercy. To the

horror of many, Laches won acquittal through these cheap courtroom antics.

In The Wasps, the case which Bdelycleon stages at home in order to

entertain and distract his father is a spoof of Laches' trial. A household dog

named Labes ("Grabber") is charged with stealing a big piece of Sicilian

cheese. Philocleon serves as the jury and behaves like a typical Athenian juryman,

complaining about things, making rude interjections and falling asleep.

Playing the lawyer for the cheese-thieving cur, Bdelycleon pleads that his

client leads a hard life protecting his master's flock and keeping his master's

sheep in line all day—sheep is surely an insulting reference to the Delian

League, the member nations of the empire the Athenians had built after the

Persian Wars—and the poor dog does not get to enjoy the usual canine

pleasures of sleeping at home all day. Labes' mate and her litter suffer from

his absence, and on cue the bitch and her pups stand up in court and bay pitifully,

going "How! How!" which is how ancient Athenian dogs said "bow-wow."

In the end, although Philocleon is reluctant to acquit the obviously guilty

hound, Bdelycleon tricks his father into putting his vote in the wrong jar,

and in the end the dog goes free.

While it constitutes one of Aristophanes' best and most original plots, The

Wasps won him only a second place. For some reason, his charm was beginning

to wear off with the public. "Well," Aristophanes must have thought,

"at least it didn't come in last place like The Clouds. But what's

wrong with these people? Why can't they accept genius when they see it. I'll

tell you what it is. It's this pointless war, that's what's really to blame.

It just keeps dragging on and on. I mean, how do they expect us to make people

laugh with all this fighting going on? Somebody should stop this stupid . .

. Wait a second! That gives me a new idea!"

5. Peace

But he didn't need a new idea, because in 421 BCE things began to change dramatically.

For one, Cleon was suddenly removed from the scene—he died in battle—and the

war-party, now beheaded, had lost its death-grip on the Athenians. Peace rose unexpectedly

on the horizon, and in that spirit Aristophanes produced a comedy

appropriately entitled The Peace at the Dionysia.

It featured Trygaeus, another commoner-hero much like Dicaeopolis in The

Acharnians, who seeks peace with Sparta. Like Dicaeopolis, too, this "average

man" is fed up with war and wants to go to Zeus himself and plead for an

end to the insane conflict. But the gods live in the sky where normal mortals

cannot go. So, to reach their abode, Trygaeus has devised an ingenious plan.

He has raised a gigantic dung-beetle on whose back he plans to ride all the

way to heaven. But to make it large enough to carry a human aloft, he has had

to force-feed it with . . . what dung-beetles like to eat. For Trygaeus' kitchen

staff, one can hardly imagine a more unpleasant task.

And so the play opens, with Trygaeus' servants

running back and forth between the kitchen and the dung-beetle's stall carrying

food items cooked up to tempt the gigantic insect's appetite. Aristophanes takes

the opportunity to wallow in the absurdity of the situation he has created by

indulging in a series of crude but uproariously funny scatological cooking-jokes.

The servants, for instance, dash in and out with courses designed to titillate

the behemoth bug's appetite and the audience's baser tastes: "crap-cakes,"

"muddy buddies," "poop-overs," "dung-in-a-blanket,"

and for dessert, not Twinkies but "Stinkies." As the audience is about

to succumb to mal-de-merde, Trygaeus himself appears riding the giant

dung-beetle to heaven on the mechane

(note). After encouraging his fellow mortals

not to do anything to attract the dung beetle back to earth, Trygaeus finally

arrives in heaven, rescues the goddess Peace, and brings her down to earth for

the collective good of all humankind.

The play, however, brought home only second prize, the second of Aristophanes'

career. More important, this joyous, if not gold-medal finale also

brings to an end a string of surviving Aristophanes comedies dating from 425-421

BCE, all securely dated via scholia which provide unprecedented data about their

times, their author and the history of ancient comedy. This depth of detail

is unparalleled in ancient theatre history, except perhaps for the Roman playwright

Terence's plays more than two centuries later.

III. Aristophanes'

Later Plays (after 421 BCE)

Though The Peace garnered only a second prize for Aristophanes, it

was a significant play for him in at least one other respect. In it he experimented

with a comic device, ridiculing Euripides, which would serve

him well in several future plays. Though The Peace was not the first

time Aristophanes had bashed the renegade tragedian—as early as The

Acharnians he had mocked Euripides' tendency to dress his heroes in rags—by

421 BCE he was clearly coming to see the general utility and applicability of

this stratagem. He later built two of his best comedies, The Frogs

and Thesmophoriazusae, by playing the anti-tragedy card. Indeed, now

that Cleon was out of the picture, grand-mal Euripidomania seized Aristophanes'

drama, attesting not only to its author's fascination with the bad boy of tragedy

but also the burgeoning popularity of Euripides' plays in the waning days of

the Classical Age (note).

1. Thesmophoriazusae

Little wonder, then, that in 411 BCE Aristophanes wrote Thesmophoriazusae

("The Women at the Festival of Demeter") in which Euripides appears

as a central character. The preposterous premise of this uproariously funny

play is that Euripides, well-known for his psychotic female characters—which

include but are not limited to murderesses, witches, liars, adulteresses, and

incestuous sluts—has heard that the women of Athens are tired of his slanders

and plan to get revenge on the seemingly misogynistic playwright. After all,

who could question why women are so angry with Euripides, since he constantly

shows them doing all sorts of nefarious and unnatural things? As it turns out,

however, that is not the problem the women in Aristophanes' play have

with Euripides.

In general, the female characters in this comedy admit freely that they do

nefarious and unnatural things, just like Euripides says. Their problem is that

their husbands, who have by now been attending Euripidean drama regularly for

decades, have started to clue into women's hidden nature and, as a result, have

become suspicious of their wives. Euripides has revealed to them how women have

affairs behind their husbands' backs and sneak wine on the side—none of

this do the women in Aristophanes deny among themselves—but now men

know it, too, and that has made it much more difficult to maintain their traditional

level of debauchery and malfeasance. The women of Athens feel they must shut Euripides down

or risk never getting away with any crimes again. So they decide to use their

annual meeting at the Thesmophoria, a sacred, females-only

festival, to plot revenge.

But Euripides is the master plotter and quickly discovers their intention.

He convinces Mnesilochus, an older male relative of his, to sneak inside the

women's rites so he can learn what the women are planning to do. But first he

needs to dress him appropriately, so Euripides and Mnesilochus go to the house

of Agathon, a notorious cross-dresser—and, of course, a

famous tragic playwright—who lets them borrow a frock. As it turns

out, he has plenty to spare.

Mnesilochus, then, goes into the women's meeting and, though "she"

watches quietly at first, cannot help "herself" when the women start

into Euripides. La femme Mnesilochus takes the floor and defends him

by noting that "she," as a woman and moreover a mother of nine, has

done all sorts of sordid things, many of which Euripides has not yet mentioned

in his tragedies. The women do not like that.

A heated debate ensues, interrupted finally by an excited messenger who reports

that Euripides has sent a spy into their midst. After an extensive search for

the intruder, the women "uncover" Mnesilochus, who, like all male

characters in Old Comedy, is wearing a phallus.

While "she" tries desperately to hide her phallus by squeezing

it between her legs, the women detect it—and him!—and thereby uncover

Euripides' latest plot.

Identified

now as the spy, Mnesilochus grabs one of the women's babies and runs in a panic

up to the altar. Desperate for his life, he threatens to kill the baby, if the

women try to hurt him, a spoof of a famous—or, better, infamous—play,

Euripides' Telephus. In this tragedy the title character seizes the

baby Orestes from Clytemnestra's arms and threatens to kill it if Agamemnon

and the Greeks will not listen to him.

Identified

now as the spy, Mnesilochus grabs one of the women's babies and runs in a panic

up to the altar. Desperate for his life, he threatens to kill the baby, if the

women try to hurt him, a spoof of a famous—or, better, infamous—play,

Euripides' Telephus. In this tragedy the title character seizes the

baby Orestes from Clytemnestra's arms and threatens to kill it if Agamemnon

and the Greeks will not listen to him.

As

Mnesilochus holds the baby aloft, he yanks the diaper off the baby and discovers

that it is not a baby at all, but a wineskin that its "mother" had

sneaked into the assembly for the party afterward. She has even put little booties

on it to make it look like a baby. Thinking he is in serious trouble now, Mnesilochus

soon discovers that sometimes you don't need a baby at all, only a bottle, since

the women are much more upset that he has their wine than they would have been

if he had taken an actual baby from them.

As

Mnesilochus holds the baby aloft, he yanks the diaper off the baby and discovers

that it is not a baby at all, but a wineskin that its "mother" had

sneaked into the assembly for the party afterward. She has even put little booties

on it to make it look like a baby. Thinking he is in serious trouble now, Mnesilochus

soon discovers that sometimes you don't need a baby at all, only a bottle, since

the women are much more upset that he has their wine than they would have been

if he had taken an actual baby from them.

Trapped at the altar with his hostage wineskin, Mnesilochus starts screaming

to Euripides for help. Then he gets a bright idea. He decides to send out a

board with a message scratched on it that says he needs to be rescued, a spoof

of another Euripides tragedy, Palamedes. It works. Euripides arrives

to save him, using a ploy from his own Helen, a tragedy produced just

the year before, and dressed as the soggy, shipwrecked Menelaus, in answer to

which Mnesilochus plays Helen. They nearly escape, except a guard arrives and

prevents Mnesilochus' departure by tying him up. Euripides slips out promising

to return.

Bound as he is to the skene building, Mnesilochus decides to try a

different trick from another recent Euripides hit, Andromeda, probably

part of the same trilogy as Helen. In this play, the hapless Andromeda

is chained to a rock near the ocean where a gigantic sea-monster is about to

come and eat her, but at the last moment the hero Perseus flies in on his winged

sandals—the mechane, of course—kills the monster and rescues

her. So, Mnesilochus begins singing a spoof of Andromeda's lament, and right

on cue Euripides arrives, flying through the air on "winged sandals."

There is much commotion as "Euri-pers-ides" attempts to land and "slay"

the guard, but in this play the sea-monster wins the battle and eventually chases

the playwright away.

Having failed to deceive his foes in typical Euripidean fashion, Aristophanes'

comic tragedian is finally forced to abandon his post-modern ways and use a

conventional, tried-and-true trick to help his hapless accomplice escape. He

walks on stage—as opposed to swimming or flying, that is—accompanied

by a beautiful dancing-girl who distracts the guard while the old man in drag

runs off. The play resolves when Euripides appeases the women by promising not

to tell their husbands, when the men return from war, all the secret things

they have been doing. The women can hardly pass up a deal like that and the

play ends on a note of concord and reconciliation.

2. Lysistrata

In the same year Thesmophoriazusae was staged (411 BCE), Aristophanes

also produced Lysistrata, another comic masterpiece

and his most popular stage piece today. This play begins with the women of Greece

holding another meeting in secret. While the men are assembling to debate the

war, the women do the same. Led by a sort of protofeminist named Lysistrata

("Shredda Garrison") who has convened and now chairs the assembly,

the women of Greece, including representatives from not just Athens but also

Corinth, Thebes and Sparta, seek their own way to end the war, a welcome opportunity

for Aristophanes to ridicule all Greek cities equally.

Lysistrata points out to her female congress that the war does nothing but

evil to everyone on all sides. There is less food, less money, less fun and,

worst of all, less sex, since the men are gone to war all the time. The foolishness

of men must be stopped, says Lysistrata, and if men themselves or the gods are

not going to stop it, the task becomes women's work. "But how can poor,

pitiful, weak, little women make big, strong men stop fighting?," asks

one of the women. Lysistrata proposes that they use their highest trump card,

their only card, in fact: they must all collectively, in one united spirit and

body, refuse to go to bed with any man until the fighting stops.

The women immediately begin to disperse, shaking their heads ("It's too

big a sacrifice for anyone to make!"). Lysistrata calls them back and begs

them to use their heads for once. "Is it so great a sacrifice, for just

a while, if we can end the war?" She leans on each one of them individually,

and finally one woman—naturally the one from Sparta who is not giving

up that much anyway, Aristophanes implies—agrees to abstain from sex in

order to end the war. One by one, the other women capitulate reluctantly and

swear an oath of chastity before the foreign women return to their cities.

The scene now focuses on Athens, where the women seize the Acropolis to protect

themselves from violent assault by frustrated men and because that is where

the war reserve of Athens had been stored, a thousand talents of gold set aside

for an extreme emergency. As long as the Athenian women hold the Acropolis,

the men cannot use the emergency funds to rebuild their navy and resume the

fighting, and in time they will find increasing frustration in terms of arms—arms

of every kind.

The make-love-not-war plan works well at first, but the sex-strike is as hard

on the women as it is on the men, if not harder. Lysistrata finds that she spends

most of her time keeping the women on the Acropolis as the men off

of it. One woman, trying to slip out, says she is only going home to "card

her wool"—that is, prepare the wool for spinning into thread—but

Lysistrata knows what she really wants to card and sends her back inside the

temple.

Another woman comes out, terminally pregnant. She says she has to leave and

go home because it is against Athenian religious law for a woman to give birth

in the temple. Lysistrata says, "Wait a second! You weren't pregnant yesterday."

The woman says, "Well, I am today. It's a miracle!" Lysistrata feels

the woman's stomach and says, "It feels big and hard." The woman exclaims,

"Bless Athena! It's a boy!" Lifting the woman's dress, Lysistrata

retorts, "No, bless Aphrodite! You've stolen the bronze helmet off the

statue of Athena, and I know why you want to go home!" And she sends the

woman and her brazen contractions back inside the temple.

But the women's woes are nothing compared to the men's suffering. Lysistrata

looks down the road that leads up to the Acropolis and sees a lone man coming

up the path. Up is the key-word here, as the man, like all men in Aristophanes'

comedies, is in an undeniable state of erotic

excitation. Lysistrata sounds the alarm that a man is coming to the gates,

to which the women respond by flocking up to get an eyeful. One of the women,

Myrrhina ("Myrtle"), recognizes the tumescent pilgrim as her

husband, Cinesias ("Mover").

Their one-on-one confrontation becomes the

deciding battle, a spoof of epic and a paradigm for the eternal conflict between

men and women. Cinesias begs Myrrhina to come down and see him but she refuses.

After much moaning and pleading and finally resorting to desperate tactics—he

says their baby needs her and pinches it to make it cry!—he convinces

her to come down from the Acropolis and meet him face to face. When she descends,

he insists that they do it, even if just it is a quickie. She says she will,

if he promises to vote to end the war.

He is clearly ready to promise her anything, and does, if she will just act

like a dutiful wife. Next, she asks him where he intends for them to do it.

He drags her off to the cave of Pan, just around the corner from the entrance

to the Acropolis (note). After taunting

her husband over and over with the prospect of sex, she ends up leaving him

alone and hard-pressed for relief. Eventually the men capitulate, give up the

war, and everyone returns home to the joys of a better sort of combat and congress.

Lysistrata is not only among the most successful comedies to come

out of ancient Greece, it's one of best ever written anywhere at any time.

Besides its brilliant comic invention, some part of this play's widespread prosperity

stems surely from the strong sense of desperation that runs beneath its mirth

and humor, the thought that the Peloponnesian War is a pointless exercise in

self-destruction. Behind the play's whimsical façade lurks a palpable

seriousness that makes Lysistrata all the easier to take seriously,

in a way very few comedies do. Clearly, the smiles on the surface of the play

mask the furrowed brows and tragic expressions of everyone in the theatre. Furthermore,

Aristophanes fits masterfully the timeless conflict of men and women onto the

time-bound war between Athens and Sparta, taking a deathless theme and applying

it to a specific situation in his Greece. Rarely has an abstract concept ever

been made more concrete and vivid in any art form and more easily translated anywhere

across time and space with less loss of relevance than Lysistrata, which

goes some way toward explaining the enduring triumph of this play.

3. The Frogs

Yet, there exists another masterpiece from Aristophanes' hand, a comedy with

a force and brilliance equaling that of Lysistrata, another testament

to this playwright's ability to distill eternal truths from temporal themes. It is his last

surviving play before the disastrous end of the Peloponnesian War, and in many

ways it is both his crowning triumph and the final dramatic masterpiece of the Classical

Age, The Frogs (note).

Like Lysistrata, a timeless hymn to the human condition, The Frogs

focuses not on sex but humanity's other great obsession: death.

By 405 BCE so many Athenians, from generals to peasants, had died in the Peloponnesian

War, it must have seemed like there was a huge Athenian party going on in the

world of the dead. Seeing little hope of regaining what had been lost, in either

material or human resources, Aristophanes set his final masterpiece in Hades,

the classical underworld, where the dead (the characters) and the living (the

audience) could join together in one last festival. It is a family reunion of

sorts for the whole Classical Age, now moribund and defunct (note).

In this bittersweet comedy, dead Athenians debate—what else would dead

Athenians do?—quibbling over what they've always debated, the debatable

merits of the ever-debating Euripides. The Frogs is, in essence, a

long and heartfelt hug good-bye to the Classical Age, for all its glories and

follies, both of which in oh-so-many ways Euripides embodied. It was also

a chance to get in one last dig at old foes, like Cleon who could realistically

be imagined to be wreaking still his own peculiar brand of hell in Hades. So,

in an infernal kommos

disguised as a komos Aristophanes

croaks a final, funereal "pity-party-song" for the past, as the present

assemble and watch the dead frolic. It is hard to imagine a play more comic

or at the same time more tragic than The Frogs. We'll examine this play in greater detail in Reading 4.

Terms, Places, People and Things to Know

|

Aristophanes

Scholia/Scholiasts [SKOH-lee-ah; SKOH-lee-asts]

The Banqueters

The Babylonians

Cleon [KLEE-yawn]

The Acharnians [ah-CAR-nee-yuns]

The Knights

The Clouds

Socrates

|

The Wasps

The Peace

Euripides

Thesmophoriazusae (Thesmophoria) [THEZ-muh-for-ree-yad-ZOO-sigh; THEZ-muh-for-ree-yah]

Lysistrata

(Lysistrata) [lie-SISS-trah-tah]

The Frogs

Dionysus (see Reading 4)

Heracles/Hercules (see Reading 4) |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Identified

now as the spy, Mnesilochus grabs one of the women's babies and runs in a panic

up to the altar. Desperate for his life, he threatens to kill the baby, if the

women try to hurt him, a spoof of a famous—or, better, infamous—play,

Euripides' Telephus. In this tragedy the title character seizes the

baby Orestes from Clytemnestra's arms and threatens to kill it if Agamemnon

and the Greeks will not listen to him.

Identified

now as the spy, Mnesilochus grabs one of the women's babies and runs in a panic

up to the altar. Desperate for his life, he threatens to kill the baby, if the

women try to hurt him, a spoof of a famous—or, better, infamous—play,

Euripides' Telephus. In this tragedy the title character seizes the

baby Orestes from Clytemnestra's arms and threatens to kill it if Agamemnon

and the Greeks will not listen to him.