©Damen,

2021

Classical Drama

and Theatre

Return to Chapters

SECTION 3: ANCIENT GREEK COMEDY

Chapter 10: Later Greek Comedy

I. Drama in the Post-Classical Greek World and the Hellenistic

Age

During the Classical Age, Greece was cast into a new and different—and

not necessarily wiser or more liveable—world. Although Athens had suffered

an ignominious defeat and the loss of the Delian League at the end of Peloponnesian

War, it quickly recovered both its autonomy and prestige, due less to anything the Athenians did and more because the victorious Spartans almost immediately proved incompetent

at managing international affairs. Their regimented way of life proved poor

soil in which to raise diplomats and, if only by comparison, Athens began to

look good in its neighbors' eyes.

Nor

was Greece polarized around Sparta and Athens any longer, as the Thebans

returned to the national scene. After nearly a century, the stigma of their ancestors having "medized"

during the Second Persian War (i.e. having voluntarily capitulated to Xerxes

and the invading "Medes") finally started to heal over. The re-emergence of Thebes precipitated a three-way

tug-of-war for power, resulting in smoldering civil strife which erupted only

intermittently into full-scale military conflict. But when conflict broke out, it

had enough force to keep any of the Greek players from expanding or even maintaining their interests abroad. The bright light of Hellenic—and particularly

classical Athenian—political and military hegemony was flickering and fading fast.

Nor

was Greece polarized around Sparta and Athens any longer, as the Thebans

returned to the national scene. After nearly a century, the stigma of their ancestors having "medized"

during the Second Persian War (i.e. having voluntarily capitulated to Xerxes

and the invading "Medes") finally started to heal over. The re-emergence of Thebes precipitated a three-way

tug-of-war for power, resulting in smoldering civil strife which erupted only

intermittently into full-scale military conflict. But when conflict broke out, it

had enough force to keep any of the Greek players from expanding or even maintaining their interests abroad. The bright light of Hellenic—and particularly

classical Athenian—political and military hegemony was flickering and fading fast.

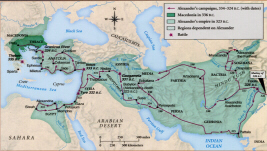

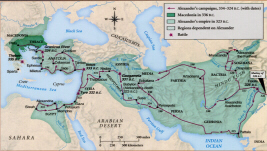

The

Greeks' cultural and commercial affairs, however, were a very different matter.

These thrived internationally, and Greek influence began to spread all around

the Mediterranean. While home was rarely a happy place—especially after

Philip II of Macedon defeated the combined forces of the Greeks

at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE—a new world and world-order dawned,

which brought with them many opportunities for economic benefit. Still, no matter

how rich one is or how hospitable the hostile forces, it's never a good day

when outsiders march in and take over one's land.

The

Greeks' cultural and commercial affairs, however, were a very different matter.

These thrived internationally, and Greek influence began to spread all around

the Mediterranean. While home was rarely a happy place—especially after

Philip II of Macedon defeated the combined forces of the Greeks

at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE—a new world and world-order dawned,

which brought with them many opportunities for economic benefit. Still, no matter

how rich one is or how hospitable the hostile forces, it's never a good day

when outsiders march in and take over one's land.

In

the wake of Alexander's conquests rose his successor generals,

the so-called diadochoi who were, in reality, little more than a succession

of petty tyrants. Their despotism proved a deathblow to the independent polis,

the civic monument that had in many ways defined the Classical Age. Its demise

was a tragedy even more devastating than the dissolution of Athenian democracy.

In

the wake of Alexander's conquests rose his successor generals,

the so-called diadochoi who were, in reality, little more than a succession

of petty tyrants. Their despotism proved a deathblow to the independent polis,

the civic monument that had in many ways defined the Classical Age. Its demise

was a tragedy even more devastating than the dissolution of Athenian democracy.

And as being an Athenian, or a Spartan, or even a Theban began to matter less

and less—and no one seemed able to make foreigners understand why that

was a bad thing—the whole ancient world including Greece was turning into

a cosmopolis engaged in trade and industry, and reciprocal conquest

and domination. A cartel of international business interests that advertised

their power through the show of military prowess was, in fact, the real power behind every throne, if anything can be said to have been. The global

situation had come to resemble a "rat race" in which a succession

of increasingly vicious, immoral and greedy rodents entered and exited the scene

so fast no one could foresee where it was heading.

Amidst all this upheaval and the inevitable vicissitudes of life in a post-modern

world, survival itself became a very difficult endeavor, entailing saving one's

own job and family from the potentially crushing chaos of perfidious fortune.

True, a Greek could make quite a lot of money, especially after Alexander's

exploits which had opened up most of the East to western exploitation—entrepreneurs

from all over the known world sold their goods in the markets of Syria and many

a Greek in search of a livelihood fought as a mercenary in the army of some

oriental despot—but to bring your winnings home to Greek soil, to live

long enough to enjoy the fruits of foreign adventure, to return like Odysseus

and not Agamemnon, that was the real challenge.

Running

the gauntlet of foreign customs and pirate kings who ruled tiny principalities

and called themselves "gods" was a matter of foolhardy daring, in

essence, to put oneself into the hands of dumb luck. Greece and its traditions,

language and literature—the very heart of Greek culture—everything

that mattered about being a proud Athenian seemed diminished in this ever-expanding

world. Everything did, in fact, look small in such an immense arena,

all except the profits one could make if one were senseless enough to head into

the rising sun and lucky enough ever to be seen again on Greek soil.

Running

the gauntlet of foreign customs and pirate kings who ruled tiny principalities

and called themselves "gods" was a matter of foolhardy daring, in

essence, to put oneself into the hands of dumb luck. Greece and its traditions,

language and literature—the very heart of Greek culture—everything

that mattered about being a proud Athenian seemed diminished in this ever-expanding

world. Everything did, in fact, look small in such an immense arena,

all except the profits one could make if one were senseless enough to head into

the rising sun and lucky enough ever to be seen again on Greek soil.

And almost the worst part about it all was the readiness of foreigners to absorb

Greek culture. Classical texts, the dramas especially, played astonishingly

well abroad, very flattering really, but it meant that barbarians started learning

the Greek language. When they ventured to speak that most fundamental tool of

Greek culture, the honeyed gift that once had lilted over the lips of Homer,

Sappho and Aeschylus, the tongue was contorted in their guttural gullets, mouths ill-tuned

to the delicate rhythms and intricate streams down which epic, lyric and tragedy had once flowed.

In a barbarian's mouth, to be frank, the language was no longer Greek but a

bastardized, international knock-off of the real thing, or, in the Greeks' own

word, koine meaning "common (speech)." A

better translation might be "vulgar."

This koine was a parlance with far-ranging impact but little of the

complex nuance on which the best of Greek literature depended, and thus the

final battleground was set. Outlanders had won the war over Greece itself some time

ago. Foreign dictators, after all, owned the land, and everyone knew there

was going to be no glorious Persian War this time, no Hellenic alliance of city-states

that would send this batch of invaders packing. The only real issue left

to resolve was who would control Greek culture. And that fight was not going

well for the Greeks, either. To lose this battle would have amounted to utter

humiliation and disgrace, total and ignominious defeat—if not for all the

money they were making, of course.

And to make matters worse, as the Greek world began moving to the beat of changing

times, the Olympian religion itself started to falter. Any level-headed person

caught in the revolutions engulfing these times could see that the

Greek gods were not in charge—or if they were, they were not looking out

for Greece, which made them either not gods or not Greek—thus, new deities

started to flood their temple squares. Isis, for example, was imported from Egypt

by sailors whose fortunes she was said to govern. From the east, Mesopotamian

astrology appealed to those who sought their destiny in the stars, or planets,

or anywhere but earth and their own choices and actions.

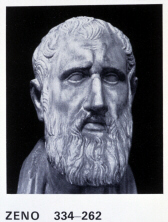

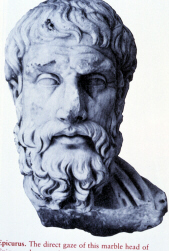

Others

parted company with heaven altogether and sought solace in logic-based

philosophies, do-it-yourself cosmologies that taught how best to deal with life's

mundane miseries, for a fee naturally—what doesn't cost in a

post-classical world?—so, for instance, Stoicism preached

an unemotional attitude to life, an "if-I-don't-care-about-it-it-can't-hurt-me"

answer to the tribulations of existence. Epicureans, on the

other hand, advocated withdrawal from the anxieties of life, harboring the notion

that one should retreat inside garden walls and forget the cold, harsh world

outside—which, as it happens, was neither cold nor harsh in Epicurus' neighborhood—and

with this, philosophy became a pain-pill, a doctor's daily injection of intellectual

morphine (click here

for more on later Greek philosophy).

Others

parted company with heaven altogether and sought solace in logic-based

philosophies, do-it-yourself cosmologies that taught how best to deal with life's

mundane miseries, for a fee naturally—what doesn't cost in a

post-classical world?—so, for instance, Stoicism preached

an unemotional attitude to life, an "if-I-don't-care-about-it-it-can't-hurt-me"

answer to the tribulations of existence. Epicureans, on the

other hand, advocated withdrawal from the anxieties of life, harboring the notion

that one should retreat inside garden walls and forget the cold, harsh world

outside—which, as it happens, was neither cold nor harsh in Epicurus' neighborhood—and

with this, philosophy became a pain-pill, a doctor's daily injection of intellectual

morphine (click here

for more on later Greek philosophy).

In

such a cultural climate, dramas delivering serious messages about local political

issues, like Aristophanes' or Eupolis' comedies, were incompatible with modern

living, as were tragedies set in a remote and by now clearly fictitious vision

of some heroic, Homeric past. Tragedy, as a result, declined precipitously.

For whatever reason—and however the cards are stacked, it was at heart

the failure of Euripides' and Sophocles' heirs—tragic drama staggered,

collapsed and moldered as a mainstream art form, evolving eventually into an

antiquarian exercise, yet another avenue of escape that some pursued.

In

such a cultural climate, dramas delivering serious messages about local political

issues, like Aristophanes' or Eupolis' comedies, were incompatible with modern

living, as were tragedies set in a remote and by now clearly fictitious vision

of some heroic, Homeric past. Tragedy, as a result, declined precipitously.

For whatever reason—and however the cards are stacked, it was at heart

the failure of Euripides' and Sophocles' heirs—tragic drama staggered,

collapsed and moldered as a mainstream art form, evolving eventually into an

antiquarian exercise, yet another avenue of escape that some pursued.

From the other side of the stage, however, comedy survived, even thrived, against all odds, but only by re-inventing itself most dramatically. No longer able to

depend on the polis for its vitality—the undoing of the independent

city-state was hardly something to joke about—Greek comic drama turned

into "New Comedy," basing its humor on the tumultuous lives of ordinary

people, though usually those considerably richer than ordinary people. Still,

in spite of a frightfully protean world, an age when so many other arts were

in turmoil and more than one fell into obsolescence and obscurity, comedy forged

on to great success, a tribute to the genius of post-classical comic poets.

II. Middle Comedy

The

radical changes in social and political conditions which rained down on Greece

in the 300's BCE led to equally elemental changes in theatre. As tragedy slowly

faded from public attention, revivals of "old" tragedies—meaning

classical fifth-century plays by Euripides and Sophocles primarily—began

to play a more central role in Greek theatre. To

put it ecologically, this left a gap in the "entertainment niche,"

which in turn opened the possibility for a new genre to rise.

The

radical changes in social and political conditions which rained down on Greece

in the 300's BCE led to equally elemental changes in theatre. As tragedy slowly

faded from public attention, revivals of "old" tragedies—meaning

classical fifth-century plays by Euripides and Sophocles primarily—began

to play a more central role in Greek theatre. To

put it ecologically, this left a gap in the "entertainment niche,"

which in turn opened the possibility for a new genre to rise.

Mime was one contender for the public's attention in that

open niche, though it didn't achieve supremacy, at least not at first (see

Chapter 11). Its bawdy, low-brow nature looked, no

doubt, simplistic to audiences nursed on the vigorous intellectualism of the

arts in the Classical Age. At the same time, however, as we noted above, the

precocious heckling of Old Comedy fared little better. As long as it had rested

in the hands of masters like Aristophanes or Eupolis and played before a restless,

idealistic democracy, it had found a way to address complex and compelling issues,

but that, as it turned out, was not always the case. As tyranny supplanted freedom,

as pragmatism displaced the search for answers to the big questions in life,

as greed won over patriotism, the playwrights of comedy had to adapt their art

to the world around them. Besides, the humor-generating formula of the "great

idea" that had driven so many of Aristophanes' plots —Lysistrata's sex strike, Euripides infiltrating an all-female festival —must have seemed not particularly funny to a society in real

need of real salvation.

What theatre was starving for was something novel and

original, but the recipe for survival was not immediately forthcoming. There

was still much middle ground to cross. Social and political issues had to settle

into some sort of scheme before drama could reflect the "new" order.

An otherwise unknown historian named Platonius preserves one

explanation for the social causes underlying the changes in post-classical drama:

. . . later . . . as power fell from the people's hands

into those of certain individuals few in number and oligarchies were prevalent,

the poets became afraid. It was not possible to ridicule anyone openly when

those who were ridiculed would sue poets in court . . . and because of this

they became more hesitant to ridicule and producers were not to be found.

And no longer were the Athenians eager to appoint producers who would pay

the expenses for choruses. For example, Aristophanes brought out Aeolosicon

which does not have choruses. Since there were no producers appointed or meals

provided for the chorus, comedy was gradually deprived of its chorus songs,

and the type of subjects it dealt with was changed. For in Old Comedy the

object ridiculed was the demagogues and jurors and generals, but Aristophanes

gave up his customary ridicule out of great fear, and criticized Aeolus,

that drama by the tragedians, as being bad. Aristophanes' Aeolosicon

is just like Middle Comedy, and so is Cratinus' Odysseuses and many

of the older comedies which do not have choruses and parabaseis.

Without a single complete Greek play—tragedy or

comedy—surviving between Aristophanes' last (388 BCE) and Menander's first

(316 BCE), there is little way for us to gauge the validity of Platonius' conclusions

or measure the evolution of what he calls Middle Comedy. (note)

Because a lack of data makes it impossible at this remove to track how Greek

drama developed over the course of the fourth century BCE, historians are left

with no other option than to skip ahead to its outcome and try as best we can

to suppose what must have happened in between. And we are not left completely

without resources, either. To wit, the history—both political and intellectual—of

this age hints at some of the processes directing this evolution.

A. Character

For example, it is commonly supposed that New Comedy,

the ultimate product that emerged from the evolution of comic drama during the

early post-classical period, arose somehow out of the many new types of philosophy

that cropped up around this time, especially ethical studies such as those

espoused by Theophrastus (ca. 370-286 BCE). His work, The

Characters, centers on the description of personality-types, mostly

unpleasant ones:

The Garrulous Man: Garrulity

is the delivery of words which are irrelevant, long and not thought out ahead

of time. The garrulous man is the sort of person who will sit down next to

someone he doesn't know, and start talking first about his wife, how wonderful

she is, and then narrate in full the dream he had last night, and then tell

what he had for dinner course by course. Now that he's warmed up, he'll say

that we're not the men we used to be in the good old days and can you believe

the price of wheat in the market and the whole city is full of foreigners

and it's a good thing we can go to sea now that it's late March and we could

sure use some more rain from Zeus Almighty and next year I'll plant this and

that and it's hard to make ends meet and did you believe the parade at the

Mysteries and have you ever counted the number of pillars in the Odeion and

I barfed yesterday and what day is it today and did you know that New Year's

comes on January first and midsummer is in July.

The Disgusting Man: Disgustingness is openly and

shamefully ridiculous behavior. The disgusting man is the sort of man who

flashes in front of married women and in the theater applauds when everyone

else is silent and boos the actors everybody else loves, and when the theater

is silent, he lifts his head up and belches so everyone turns around and looks

at him. He calls by name people he doesn't know, and if anyone is in a hurry,

he tells them to slow down and wait for him . . .

From the comical nature of these analyses of "character," it is often

assumed that Theophrastus' brand of philosophy stimulated the character-driven

drama that propels most New Comedies. Certainly, grumpy old men, love-sick youths,

crafty slaves and their ilk—the typical denizens of later Greek comedy,

especially Menander's—are part and parcel of Theophrastus' "psychological"

way of reflecting on human life.

Of

course, the chronology of all this is fuzzy, as is so often the case in ancient

studies, and therefore the reverse is also possible. In other words, dramatic

comedy may have fostered Theophrastus' philosophy of "character,"

since we simply do not know which preceded which. If anything, the dating argues

for theatre's primacy, since several comic character-types—in particular,

the braggart, the coward, the managing slave, and so on—are visible in

theatre as early as the fifth century, well before Theophrastus' lifetime.

Of

course, the chronology of all this is fuzzy, as is so often the case in ancient

studies, and therefore the reverse is also possible. In other words, dramatic

comedy may have fostered Theophrastus' philosophy of "character,"

since we simply do not know which preceded which. If anything, the dating argues

for theatre's primacy, since several comic character-types—in particular,

the braggart, the coward, the managing slave, and so on—are visible in

theatre as early as the fifth century, well before Theophrastus' lifetime.

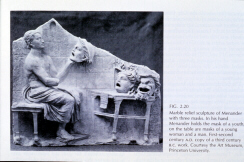

Moreover, the sense of unchanging personality type is

a natural extension of classical theatre, where masks "freeze" a dramatic

character in one expression and, thus, one emotional mode. As a result, angry

old men will always look old and angry on stage when actors wear masks depicting

them that way. It's not much of a leap to assert, then, that the emotions so

easily read in their frozen expressions are emblazoned with equal rigidity on

their minds as well. (note)

This, then, leaves open the question of where and how personality-centered

comedy arose. The truth is that it goes back as far as can be seen in Greek

literature. Homer includes typical comic characters, such as the abusive misanthrope

(Thersites) and the scheming wife (Hera). For us, however, the issue revolves

not around these characters' ultimate origin, but when they first entered the

stage and who was responsible for giving them a dominant role in theatre. While

Aristophanes and his contemporaries almost certainly recognized and played on

stereotypical characters, Old Comedy did not rely upon them as a driving force.

Ideas, not characters, ruled comedy in the Classical Age.

B. The Nature of Middle Comedy

The change from idea-driven to character-driven comic drama must have transpired

at some point during the long and murky medieval age known now as Middle Comedy

that spans most of the fourth century BCE. It would be helpful, then, to review

plays from this period but since no complete play survives—only titles

and fragments—we are left mostly in the dark. To judge from what pitiful shards

exist, it is clear no single type of comedy defined this age. In some ways,

the evidence suggests Middle Comedy looked back to its forebears in the Classical

Age. For instance, current politicians and well-known figures were pilloried,

just like in Old Comedy, but probably not as directly, centrally or vigorously

as Aristophanes and Cratinus had done.

If, however, any type of drama predominated in Middle Comedy, it was the mockery

of classical myth and tragedy—particularly Euripides—another

sort of backwards glance. But in spoofing Euripides, Middle Comedy playwrights

were, in fact, not just ridiculing him but also reappropriating his plots, characters

and dramatic dynamic for their own purposes, a grand display of flattery if

ever there was. Indeed, Euripides' influence on later Greek comedy is arguably

the greatest of all fifth-century dramatists, even Aristophanes'.

Other notable trends in Middle Comedy are more forward-looking. For instance,

in Aristophanes' last two extant plays, the role of the chorus is severely diminished, which is in line with a general pattern of evolution across the century. By Menander's

day, in fact, the chorus had declined so far that choral odes were completely

disconnected from the main play, which means that at some point during the evolution

of Middle Comedy they must have fallen entirely out of the purview of playwrights who stopped composing songs altogether. Nevertheless, Greek drama still retained

choral odes, just not new ones composed specifically for a play's debut.

Choristers, instead, sang embolima

("inserted [songs]," literally "things thrown in"). A "throw-in" is Aristotle's way of referring to a song not composed

for a particular drama but imported into it from other sources. These embolima were

ultimately noted in the text with a perfunctory designation, "chorou,"

Greek for "the chorus' (song)." (note)

When later the custom arose of inserting these at four intervals in the play,

a tradition was born that plays should consist of five discrete acts, the so-called

five-act rule seen in not only Greek New Comedy but also later

Roman tragedy, and even as late as French classical drama in the modern age.

(note)

While this signals to some the demise of the chorus as an integral feature

of drama, it is wise not to assume too much here. If Aristotle appears to deprecate

these embolima, it does not mean they had no dramatic value whatsoever

or no affiliation with the play being presented on stage. Embolima

could always have had a thematic or analogical tie to the main storyline of

the drama. Besides, the fact that music and dance maintained their presence

on the post-classical Greek stage, even after being dissociated from the play

itself, argues strongly that the Greek audience still wished to see choreographed songs on stage. Perhaps, it constituted an advantage to post-classical Greek

dramatists, like many of their modern counterparts, that they no longer had

to be musicians and lyricists as well as poets and dialogue-makers. That surely

opened up playwriting as a career to a wider range of talent. The long and short

of it is, the evolution of Middle Comedy makes it clear that the Greeks were

well on the way to inventing the "variety hour."

Along with "connected" choruses out went the parabasis,

too, the Old Comedy playwright's opportunity to address his audience directly

and comment on current events and modern life. In tune with the changing times,

satirical elements were, in general, downplayed, as were the crudities and raw

humor so prevalent in Aristophanes' day. And so among other casualties, the

phallus sang its schwanz song.

Instead, the prominence these elements had once played in Greek comedy was now handed over to a melange

of characters based on dramatic stereotypes: the love-sick young man, the clever

slave, the greedy prostitute, the braggart soldier, the miserly old man, the

talkative cook, the scheming pimp, and all the rest "here on Gilligan's

Island." How, when and by whom these types were introduced to the

comic stage is a question we cannot answer satisfactorily given the evidence

at hand, but even though fragmentary, the data leave behind enticing hints.

One of the playwrights who the evidence suggests was instrumental

in this transition was Alexis of Thurii, the greatest exponent of comic drama during the Middle

Comedy period. While no play of his survives

complete, one hundred and forty titles and over three hundred fragments of his

comedies attest to both his popularity and longevity as an artist. (note)

The evidence hints at his use of intrigue and deception in his plays—both

are well-known features of New Comedy—and he was probably involved in

their integration into drama one way or another. Thus, though a pivotal figure

in the history of theatre, Alexis' image is little more than a tantalizing silhouette

hanging between the portraits of Aristophanes and Menander.

It has been surmised, for instance, that his play Parasitos

("The Parasite") contained the prototype of what would become one

of the most popular characters in New Comedy, the parasite.

(note) In origin, a priest's helper who

sat beside him at meals and assisted in the administration of a sacred banquet,

the parasite turned under Alexis' guidance into a kiss-up and hanger-on, the

companion of rich people who feed him in return for amusement and flattery.

Thus, if not the founder of New Comedy itself, Alexis appears to have crafted

one of the most prominent and successful characters in its portfolio.

It is all the more tragic, then, that none of this dramatist's plays survives.

Though it has been suggested that the Roman comic playwright Plautus adapted

his comedy The Little Carthaginian (Poenulus) from an original

by Alexis, such speculation only opens a rat's nest of further questions about

the relationship between Greek originals and Roman adaptations. Still, even

if Alexis' history is lost in this dark age of comedy, it is evident his shadow was, in more

ways than one, a long one.

Finally—and it is perhaps the most important thing to note about this

period of theatre history—of the over fifty Middle Comedy playwrights

whose names are cited in our sources, quite a few were not native-born Athenians.

The cosmopolitan life of post-classical Greece had clearly begun to make an impact

on Greek society by then, and the arts naturally followed in tow. That is, as

the fourth century BCE came to a close, the stage door of the Theatre of Dionysus

had admitted a pool of talent imported from far beyond the immediate vicinity

of Attica. The skene was now as much a cosmopolis as the theatron,

just like Athens itself and the rest of the Hellenic world.

III. New Comedy

In the 320's BCE, the ravages that had followed in the wake of Alexander's

conquests opened the door even wider for the revolution in lifestyle already

underway. So, it comes as no surprise that in the Hellenistic Age there developed

a new type of theatre, engineering a change that would forever alter the gaze on comedy's mask. The focus of drama shifted to the fears and foibles of average—and

by that, read "richer than average"—people in Athens, in particular,

their struggles to keep family and fortune alive. In the process of this evolution,

later Greek comedy created a vision of life very different from that of Old

Comedy.

This "New Comedy" came to depend not on the mad,

ebullient hopes of renegade reformers like Aristophanes' Dicaeopolis

or Lysistrata, dramatis personae

consumed with some great notion about how to cure society's ills, but relied

instead on the fortuitous favors of a hostile world run on luck and money. Indeed,

coincidence dominates New Comedy, but, one should note, only slightly more

than it does the real world. Unlike its real-life counterpart, however,

this genus of fortune is kind, clear-sighted and moral. Long-lost children end

up living next-door to their grieving parents, young men compromise women who

seem to be prostitutes but fortuitously turn out to be marriageable maidens

in love with their attacker, and gentile courtesans welcome home nubile virgin

sisters to the lusty arms of well-meaning and well-endowed Athenian bachelors.

It is as if the world were made of nothing but Euripidean rescue-plays.

The message of New Comedy seems to be that Fate will in time take care of the

beleaguered, if only they're patient and await salvation. Gods, if they cameo at all on

the stage of New Comedy, are less likely to hail from the traditional Olympian

caucus than the halls of academe where pseudo-scientific deities like Philemon's

"Air" or Menander's "Ignorance" rule. To wit, a goddess

named Misapprehension delivers the prologue of Menander's Perikeiromene

("The Shorn Girl" or "The Rape of the Locks"). It makes sense that personified

abstractions would rule a philosophical era like the Hellenistic Age. Thus,

no longer do gods in the traditional sense bring salvation, but it is the consideration

of stars that redeems the suffering of those who sit at home and watch and hope

and reason.

As a result, the post-classical theatre was both a grim

reflection of the darkling world around it and at the same time a haven from

the storm outside—or, at least, a brief respite from glowering reality.

An accurate but never too detailed picture of the world it inhabited, New Comedy

eventually became a way of life unto itself, to the point that one ancient critic

asked about Menander, the greatest of New Comedy poets: "Menander or Life?

Which imitated which?" (note)

Whatever the "Man" answer to this Sphinx's enigma, comedy evolved into one

of the driving forces of later Greek society, especially after Alexander's devastations.

For all the attention paid to drama in the fifth-century BCE with its three

famous tragic playwrights, the succeeding centuries were the real classical

age of theatre, at least to judge from the extent and intensity of interest

in theatre across the ever-spreading, ever more diffuse Greek world.

As

such, the precepts of Greek theatre, such as the three-actor and five-act "rules,"

came to be well-known far outside Athens. Dramatists far and wide played intelligently

with these conventions and with traditional Greek character-types, to the point

that only one of the consummate masters of New Comedy was an Athenian by birth,

Menander. His greatest rival, Philemon (ca.

368-267 BCE), a close contemporary of Alexis, hailed from the Greek world outside

Athens, as did his slightly younger comrade Diphilus (ca. 360-290

BCE) who was born in Asia Minor—not that either lived as an adult anywhere

but Athens which was still the magnet that attracted dramatic talent from all

quarters—the point is, neither was a native-born Athenian. The trio of

Menander, Diphilus and Philemon became the most famous playwrights of Greek

New Comedy, a post-classical comic triad comparable to the tragic trope of Aeschylus, Sophocles

and Euripides.

As

such, the precepts of Greek theatre, such as the three-actor and five-act "rules,"

came to be well-known far outside Athens. Dramatists far and wide played intelligently

with these conventions and with traditional Greek character-types, to the point

that only one of the consummate masters of New Comedy was an Athenian by birth,

Menander. His greatest rival, Philemon (ca.

368-267 BCE), a close contemporary of Alexis, hailed from the Greek world outside

Athens, as did his slightly younger comrade Diphilus (ca. 360-290

BCE) who was born in Asia Minor—not that either lived as an adult anywhere

but Athens which was still the magnet that attracted dramatic talent from all

quarters—the point is, neither was a native-born Athenian. The trio of

Menander, Diphilus and Philemon became the most famous playwrights of Greek

New Comedy, a post-classical comic triad comparable to the tragic trope of Aeschylus, Sophocles

and Euripides.

Like Euripides, however, Menander eventually emerged triumphant

from that threesome—he was later dubbed the "Star of New Comedy"—yet

he never knew that victory since it came only after death. Philemon, we are

told, during their lifetime won more first-place awards than Menander at the

Lenaea and the City Dionysia. It would be lovely, then, to compare for ourselves

the quality of their handicraft but we cannot, because only a handful of Menander's

and none of Philemon's comedies survive, at least in Greek. (note)

To judge from what little remains of the original texts, Philemon seems to have

dwelt at some length on philosophical issues that happened to be currently in

vogue, which would go some distance to explaining his popularity in his day

and the subsequent loss of interest in his drama once those issues had passed

from immediate public attention.

Diphilus' comedy is no easier to gauge—as with Philemon,

only tattered remnants of his works survive in Greek—even though both

Plautus and Terence, Roman comic playwrights living a century or so later, adapted

Diphilus' work. (note) If any single thing

stands out as characteristic of Diphilean comedy in both the vestiges of his

comedies in Greek and their later Roman adaptations, it is a flair for broad

comedy and farcical violence in keeping with Aristophanes' love of strong dramatic

effects on stage. Curiously, then, if anyone on the post-classical Athenian

stage was Aristophanes' immediate heir, it was not his native countryman Menander

but Diphilus who hailed from the Greek city of Sinope on the southern coast

of the Black Sea.

A. Menander

[Click here

for a brief overview of Menander's drama in the Cambridge History of Classical

Literature (pdf file). The material in the this article will NOT be used

on the Quizzes or Tests in this class. I include it only for your edification and enjoyment.]

In

any case, Menander became not only one of the greatest playwrights of all antiquity,

but one of the most lauded Greek writers ever. The critic Aristophanes of Byzantium,

for instance, ranked Menander "second only to Homer" among all ancient

authors—high praise, to say the least. Though Menander's plays failed to be copied

in the Middle Ages for reasons having nothing to do with the quality of his

drama, the sands of Egypt have rendered up many Menander papyri, attesting to

his enduring popularity even centuries after his lifetime. (note)

One all-but-complete drama (Dyscolus, "The Grouch")

and several others preserved in various degrees show that Menander continued

to be read not only in the great urban centers of Greek and Roman civilization

but also on the geographical and cultural periphery of the ancient world. That

is, as long as the ancients sought out Greek literature for either wisdom or

pleasure, Menander was seen to instruct and delight.

In

any case, Menander became not only one of the greatest playwrights of all antiquity,

but one of the most lauded Greek writers ever. The critic Aristophanes of Byzantium,

for instance, ranked Menander "second only to Homer" among all ancient

authors—high praise, to say the least. Though Menander's plays failed to be copied

in the Middle Ages for reasons having nothing to do with the quality of his

drama, the sands of Egypt have rendered up many Menander papyri, attesting to

his enduring popularity even centuries after his lifetime. (note)

One all-but-complete drama (Dyscolus, "The Grouch")

and several others preserved in various degrees show that Menander continued

to be read not only in the great urban centers of Greek and Roman civilization

but also on the geographical and cultural periphery of the ancient world. That

is, as long as the ancients sought out Greek literature for either wisdom or

pleasure, Menander was seen to instruct and delight.

In that and other respects, he was the Shakespeare of sorts for his day. Both

dramatists, for instance, brought wit and subtlety to the portrayal of conventional

character types as a means of commenting intelligently on human life. Where

the Bard created Shylock, Othello and Kate, the Star of New Comedy took the

stereotype of the greedy prostitute and turned her into a shrewd but caring

madam who hides her good heart behind a façade of fierce commercialism.

Similarly, Menander's bragging soldiers dwell not just on how many enemies they

have killed but also how well they treat the woman they love—or would,

if she gave him half a chance. His managing slaves let people call them clever

because they wish they really were. Like in Shakespeare, Menander's characters

are both frail and resilient, a meticulous mix of theatre and reality.

As Menander's dramatis personae search for sense amidst the chaos

of a confounding world, they find their best path to safety within themselves,

inside their own "characters." In the end, despite all their shortcomings

and the tragedies they suffer which are all too often from their own making,

some kindly deity—usually an idolized ideal like Ignorance or Persuasion—looks

down on them, laughs gently and nudges them down some obvious, open path toward

salvation. Like only a handful of writers in all of history—the short

list of truly great authors like Dante, Vergil and Homer—Menander strikes

and holds that most difficult of poses, the delicate arabesque between looking

honestly at the horror and heartbreak of humanity and seeing a reason to hope,

even chuckle.

As

more and more of Menander's work comes to light, his standard modus operandi

becomes clearer. He regularly played on his audience's expectations that certain

character-types act in predictable ways. His sons are typically headstrong,

their fathers too concerned with money and status, and their servants prone

to go off on their own and carouse when they think no one is watching. But Menander

also experimented profitably with these stereotypes—and not just by inverting

the viewer's conventional perspective of these characters as

Sophocles was inclined to do—but by giving the characters themselves a sense

that they are "character-types" and are expected to act accordingly.

When they naturally resist being hemmed in by others' perceptions of what they

will do or think—and who doesn't hate to be labeled?—they take on

unexpected and vibrant dimension, appearing as rich and layered humans. It is

as if Antigone in the midst of her quarrel with Creon were to say, "Uncle,

I'm tired of being so righteously indignant! Aren't we both trying to do what's

right? Can't we just talk like people, not Antigone and Creon?"

As

more and more of Menander's work comes to light, his standard modus operandi

becomes clearer. He regularly played on his audience's expectations that certain

character-types act in predictable ways. His sons are typically headstrong,

their fathers too concerned with money and status, and their servants prone

to go off on their own and carouse when they think no one is watching. But Menander

also experimented profitably with these stereotypes—and not just by inverting

the viewer's conventional perspective of these characters as

Sophocles was inclined to do—but by giving the characters themselves a sense

that they are "character-types" and are expected to act accordingly.

When they naturally resist being hemmed in by others' perceptions of what they

will do or think—and who doesn't hate to be labeled?—they take on

unexpected and vibrant dimension, appearing as rich and layered humans. It is

as if Antigone in the midst of her quarrel with Creon were to say, "Uncle,

I'm tired of being so righteously indignant! Aren't we both trying to do what's

right? Can't we just talk like people, not Antigone and Creon?"

But such complex drama presupposes the viewers can associate a character with

a particular situation or emotional state, that they expect a person on stage

to act in certain ways. It helps in making that happen—in fact, it is

all but mandatory—to have a body of myth in which specific names are linked

to certain acts: Medea to witchcraft, Orestes to matricide, Helen to Paris-bonding.

But Menander was not working with Greek myth the way Sophocles and Euripides

were. As it turns out, however, he had something nearly as good.

Across the mysterious fourth-century there evolved in Greek comedy a roster

of dramatic characters who were associated with fairly predictable activities.

What is more important, they were also attached to specific names, in much the

same way the mere mention of Odysseus brings to mind notions of deception and

intrigue, or Achilles the image of youth and anger. This slate of comic characters

and their typical exploits provided Menander with a "mythology" much

like the tragedians had, from which he could play with or against the audience's

expectations and create dramatic tension.

For

instance, in even what little remains of Menander's comedy, the character-name

Moschion ("Bull-Calf") is attached at least seven

times to a particular kind of character: a hot-blooded youth who is often responsible

for compromising and impregnating a young woman, often forcibly. (note)

Another recurrent type associated with a particular name is Demeas

("People"), invariably an irascible old man who disapproves of irresponsible

adolescents like Moschion, even though they are often close relatives. Smikrines

("Small") is another such character, also aged but more miserly in

disposition than Demeas. Menander repeatedly sets him at odds with yet another

habitué of Menandrean comedy, a slave named Syros ("Syrian")

who serves as a household butler and often knows what's going on at home better

than anyone including his master. It is the glory of Menander that he took what,

no doubt, started out as flat comic caricatures and molded these cartoons into

subtly realistic stage personas whose geniality comments brilliantly on the

human condition, in particular the ecstasy and toils of love.

For

instance, in even what little remains of Menander's comedy, the character-name

Moschion ("Bull-Calf") is attached at least seven

times to a particular kind of character: a hot-blooded youth who is often responsible

for compromising and impregnating a young woman, often forcibly. (note)

Another recurrent type associated with a particular name is Demeas

("People"), invariably an irascible old man who disapproves of irresponsible

adolescents like Moschion, even though they are often close relatives. Smikrines

("Small") is another such character, also aged but more miserly in

disposition than Demeas. Menander repeatedly sets him at odds with yet another

habitué of Menandrean comedy, a slave named Syros ("Syrian")

who serves as a household butler and often knows what's going on at home better

than anyone including his master. It is the glory of Menander that he took what,

no doubt, started out as flat comic caricatures and molded these cartoons into

subtly realistic stage personas whose geniality comments brilliantly on the

human condition, in particular the ecstasy and toils of love.

There is, in fact, no known play of Menander's that does not deal with eros

("love") in some respect. Though it may seem trite to us,

the argument that seems to have pervaded his corpus of drama—that fathers

ought to let their children pick a mate instead being married off against their

will—was quite revolutionary in Menander's day and bespeaks his gentle

compassion for all ages and aspects of life. Thus, both his characters and themes

are universal, which surely accounts, at least in part, for his long-lasting

fame.

B. Samia

There is no better example of this than Menander's Samia

("The Woman from Samos"). In this play, the ever-excitable Moschion

has impregnated an innocent young woman who lives next-door and she has given

him a child. Though neither his father (by adoption) Demeas nor the young woman's

father Niceratos know about the baby because it was born while they were abroad

on a business trip together, they have arranged for Moschion and the young woman

to marry. So, while no one in the play as yet knows it, the drama contains within

itself an easy resolution—the young parents are destined to be married—which

should work itself out readily when the fathers return home.

But easy ways are rarely human ways—and thus they

win no part in a Menandrean comedy—because in both life and Menander,

"character" not only provides but also impedes the easy resolution

of our troubles. That is, who we are all too often forestalls and simultaneously delivers our rescue

in the same slow, ineluctable stroke. In this case, Moschion dreads confessing

the problem he has engendered, because he is well aware how quick to anger Demeas

can be and he fears the consequences of his father's wrath—adoptive relationships

are at times more delicate than those between a birth parent and child—or

so Moschion lets himself believe.

In reality, Moschion's pride and awareness that his behavior has been irresponsible

prevent him from doing what is right and obvious, admitting the full truth.

Instead, like so many teenagers then and now, he decides to lie, in this instance,

to try and pass the child off as another woman's, his step-father's new mistress

Chrysis ("Goldie"), until he can find the right moment

and muster up enough courage to tell the old man what really happened. (note)

Chrysis agrees, because she has herself just lost a baby in a miscarriage and can easily nurse

the child, and as a woman who has often seen eros lead youth astray,

she feels compassion for the situation into which the lovable, handsome and

headstrong Moschion has gotten himself.

The gods let this feeble plan limp along, far further than it deserves—we

earn more of their mercy than we should but who's to say why?—and Moschion

hangs onto his story until at last Demeas stumbles upon a reason to suspect

far worse of the boy than what he actually did. Overhearing some maids talking,

Demeas learns that his beloved ward is the father of the baby and naturally

concludes that his woman Chrysis calved her kid by Moschion. How hard is it,

after all, to believe that impetuous young men like Moschion are capable of such

heinous acts, or that reformed "professionals" of Chrysis' ilk would

conspire with them and delude an older lover?

Armed with half the facts and smouldering with that caustic rage symptomatic

of senescence, Demeas explodes in indignation, not at his treasured ward however—that

Gorgon is too dreadful to look in the face so soon after learning such a terrible

truth—but at Chrysis. Women and children make much easier targets for

alpha males at moments like this, and so Demeas hauls her out of his house and evicts

both her along with her baby. When Moschion hears this, he realizes what he

has done and decides finally to tell his father the full truth, on the adolescent

logic that it is better to confess late than never and take the rap for the

lesser crime he really committed instead of the unconscionable act of infidelity

his lie has accidently branded upon him.

So finally in Act Four Moschion does what he should have done several choral

interludes earlier—and who of us has not arrived at honesty a few chorou's

too late?—he tells Demeas the whole, unwholesome truth. At last wrapping

his mind around a sin far less damnable than his initial fear, Demeas calms

down and saves the situation by consenting to do what he had decided on long

ago, have Moschion marry the girl next door who is, after all, the mother of his child. It is, by all fair standards, a proper wedding and

a proper wedding night, just not in that order! And all along, the only real

obstacle to this happy ending has been character, that heavenly gift which so

often saves us and so often stands between us and the fulfillment of our joy.

And there the play should end, but not in Menander's universe. Things are never

so simple as a happy ending, not in a world filled with "characters"

like us. In Act Five, the final act of the drama, Moschion's feelings again

take center stage, this time hurt and resentful that his adoptive father did

not trust him but instead suspected him of a terrible betrayal of trust. So,

in spite of the fact Moschion's own actions prove Demeas had good reason to

doubt his ward's honor and despite the happy resolution of his love

affair, Moschion decides to punish his father by leaving home and joining the

army—young people are impulsive, if nothing else—and even if he

doesn't really mean to do that, he will at least threaten it, just to show Demeas

how badly he was hurt.

Only after Demeas publicly admits he was wrong—he does not, in fact,

apologize or actually say "I'm sorry"—and in typical paternal

fashion lectures Moschion about pre-judging people, only then does the proud

young man at last relent and grasp the happiness life has been trying to hand

him for most of this very long drama-day. Stepson and stepfather are reunited, proving

that a few minutes of earnest listening at the end of a stressful growth-spurt

can go some way toward appeasing a pathological adolescent. In the end, such

kindly advice and insight into human life characterizes Menander as one of the

most perceptive and thoughtful observers of our species. And while the picture

he paints of our kind is hardly flattering, though largely accurate, his drama

leaves behind the impression that he—and the gods!—might possibly

really, in spite of all our ridiculous flaws, like us.

Terms, Places, People and Things to Know

|

Thebans (Thebes)

Philip II of Macedon

Alexander

Koine [KOY-nay]

Stoicism

Epicurean(s)

Mime

Platonius [pluh-TONE-knee-yuss]

Middle Comedy

Theophrastus, The Characters [thee-yoh-FRASS-tuss]

Character

Euripides

Embolima [em-BOWL-lee-mah]

Chorou [CORE-roo]

|

Five-Act Rule

Alexis of Thurii [THURR-ree-yee]

Parasitos (Parasite) [pair-ruh-SEE-toss]

Menander [men-NAND-derr]

Philemon [fill-LEE-mahn]

Diphilus [DIFF-fill-luss]

Dyscolus [DISS-cuh-luss]

Moschion [MOSS-key-yawn]

Demeas [DEEM-mee-yuss]

Smikrines [SMY-kree-neez]

Syros [SIGH-russ]

Samia [SAY-mee-yah]

Chrysis [KRISS-siss] |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Nor

was Greece polarized around Sparta and Athens any longer, as the Thebans

returned to the national scene. After nearly a century, the stigma of their ancestors having "medized"

during the Second Persian War (i.e. having voluntarily capitulated to Xerxes

and the invading "Medes") finally started to heal over. The re-emergence of Thebes precipitated a three-way

tug-of-war for power, resulting in smoldering civil strife which erupted only

intermittently into full-scale military conflict. But when conflict broke out, it

had enough force to keep any of the Greek players from expanding or even maintaining their interests abroad. The bright light of Hellenic—and particularly

classical Athenian—political and military hegemony was flickering and fading fast.

Nor

was Greece polarized around Sparta and Athens any longer, as the Thebans

returned to the national scene. After nearly a century, the stigma of their ancestors having "medized"

during the Second Persian War (i.e. having voluntarily capitulated to Xerxes

and the invading "Medes") finally started to heal over. The re-emergence of Thebes precipitated a three-way

tug-of-war for power, resulting in smoldering civil strife which erupted only

intermittently into full-scale military conflict. But when conflict broke out, it

had enough force to keep any of the Greek players from expanding or even maintaining their interests abroad. The bright light of Hellenic—and particularly

classical Athenian—political and military hegemony was flickering and fading fast.