©Damen,

2021

Classical Drama

and Theatre

Return to Chapters

SECTION 1: THE ORIGINS OF WESTERN

THEATRE

Chapter 4: The Origins of Greek Theatre, Part

1

I. Introduction: Standard Views of the Origin of Greek

Drama

The standard views of the origin of Greek drama

and theatre center for the most part around three distinct and incompatible

pieces of data: (1) accounts concerning Thespis who is the purported "inventor"

of tragedy, (2) the meaning and evolution of the Greek word tragoidia

("tragedy") and (3) the historical account of early Greek theatre

found in the fourth chapter of Aristotle's Poetics.

• That is, some ancient sources report that tragedy was the invention

of a person named Thespis who was famous for riding around in a cart and performing

dramas.

• Others see an important clue to tragedy's rise in the Greek word

tragoidia, meaning literally "goat-song," and from that

assume a goat was the prize for the winning playwright at primitive Greek

festivals featuring drama. In the words of Oscar Brockett, one of the pre-eminent

theatre historians of the modern age, "the chorus danced either for a goat as

a prize or around a goat that was then sacrificed." (note)

• Finally, the renowned fourth-century (i.e. post-classical) philosopher

Aristotle, the first person we know to have researched the origins of drama,

concluded in his famous work on drama and theatre, The Poetics, that

tragedy evolved out of another form of performance popular in the day, a type

of choral singing called dithyramb.

As we will see, there is much that can be said in opposition to all these assertions,

so much that no real hope exists of achieving consensus by using these data.

A. Thespis

First,

except for what we are told concerning the origin of drama, Thespis

is entirely unknown, a name that means essentially nothing to us except as the

purported founding father of Greek drama. Worse yet, all sources that talk

about him are late, none even vaguely contemporary. For instance, our information

about his cart comes primarily from Horace, a Roman poet who wrote more than

half a millennium after the age when Thespis would have lived. Moreover,

that very few earlier sources mention him is particularly troubling if indeed

we are to ascribe to him the invention of tragedy.

First,

except for what we are told concerning the origin of drama, Thespis

is entirely unknown, a name that means essentially nothing to us except as the

purported founding father of Greek drama. Worse yet, all sources that talk

about him are late, none even vaguely contemporary. For instance, our information

about his cart comes primarily from Horace, a Roman poet who wrote more than

half a millennium after the age when Thespis would have lived. Moreover,

that very few earlier sources mention him is particularly troubling if indeed

we are to ascribe to him the invention of tragedy.

All this makes him sound more like a fabrication of later ages attempting to

simplify theatre history by assembling what scant data there are under one name,

in much the same way that young children in America are taught "George

Washington was the founding father of the United States." Yet historians

will note that the reality of early America is vastly more complicated, involving

hundreds, if not thousands, of "founding fathers." The aggrandizement

of George Washington is a way of simplifying the complex history of the American Revolution for those who have little room in their lives for the actual and

complex realities of the past. Is Thespis' role in history comparable?

The historicization of George Washington can be telling in other ways as well.

For one, the American general actually existed and is not a fictitious icon.

One might conclude the same about Thespis except that there is no primary evidence

for his existence as there is for the American founding fathers—the records

of the Pre-Classical Age were scant, even in antiquity—thus, it would

have been much easier back then to concoct a Thespis than it would be today

to counterfeit a George Washington. Moreover, that very lack of evidence would

also have driven the need to explain tragedy's origin somehow. One simple solution

to the innocent question, "Where did Greek drama begin?," would have

been to personify the complex evolution of early Greek theatre by forging a fictional "founder," making it easier in general to make a long and convoluted

past coherent.

Whatever the truth, by all fair standards of history, Thespis is undated, unattested,

and unassociated by any credible primary source with any particular practices

in early theatre. In other words, except for the legends surrounding his name, we have no outside

corroboration even of his existence, much less his contribution to drama. If

he resembles any personage in the "forest primeval" of America, it

is Evangeline or Paul Bunyan, not George Washington.

B. Tragoidia

Second, the Greek word tragoidia presents even more

of a mystery. That it means "goat (trag-) song (-oidos)"

is certain because there is no other way to interpret the word satisfactorily

in Greek, but to what the "goat" refers is not at all clear. Goats

are not known as prizes for winning playwrights in any other ancient venue,

nor would one make a very attractive reward. Frankly, one hopes ancient playwrights

competed for something a bit more becoming. Goats, in fact, feature nowhere

in the extant primary records of ancient Greek theatre, so to conclude that

they were sacrifices, as Brockett and others do, is pure speculation. Still

there is no writing off the goats entirely, the way one can with Thespis, because

"goat" is firmly anchored in the very name of the genre and that term goes back to the origin itself of the artform.

The desperation of this situation has led otherwise

conservative and judicious critics to make uncharacteristically wild guesses

at the reason goats are found grazing around the ancient stage. For instance,

Margarete Bieber suggests that "goats" may be a nickname for the worshipers

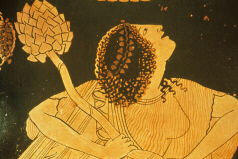

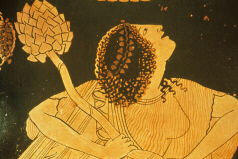

of Dionysus, the god in whose honor drama is performed at Athens. (note)

While it is true that such nicknames exist for the adherents of other gods,

for example, "bears" or "bees" for devotees of Artemis,

there is no such recorded appellation for the celebrants of Dionysus. In fact,

few gods beside Artemis have worshipers with nicknames—it seems to be

something largely peculiar to her cult—so, on closer examination, the

extrapolation stands on shaky ground.

Another avenue leads to more productive results.

Some scholars have suggested that "goat-song" may refer

not to goats as such, but to an ancient Greek slang term, "to goat,"

referring to the breaking or cracking of a young man's voice during puberty.

(note) If ancient tragic choruses were

performed by young men, this could make an odd sort of sense. (note)

The term tragoidia would then be a joke, based on the cracking of the

young men's voices—though not during an actual performance, one hopes!

Names for dramatic genres are, in fact, known to be based on jokes elsewhere,

for instance, the modern performance genre called "soaps." After all,

could the reason for the name "soap" be easily reconstructed two millennia

from now, if it were not known that there was once a connection between daytime

drama and the detergent industry which provided the funding for soap operas? Without such knowledge, future scholars might

reach for simplistic but reasonable-sounding explanations, such as, "These

emotional melodramas were seen to ‘cleanse' the soul, and thus the genre

came to be called 'soaps'." It would be much harder to recreate the

real reason for the name, that it is essentially an ironic jab at the early

commercialism of this art form. All in all, the reason why there are goats in

tragedy is an unresolved conundrum, though in light of theatre and ancient history

the "goating voice" explanation makes better sense than suggesting

that goats once served as prizes.

C. Aristotle's Poetics

Third, Aristotle and the theory of the origin of Greek drama he presents in his treatise on theatre, The Poetics,

deserves to be read in full.

Aristotle, The Poetics, Chpt. 4.1-6

(1449a) [The Poetics, according to one modern commentator, "is

often elliptical in expression, and some of its ideas seem inadequately, at

times almost incoherently, developed." (note)

Thus, it is hardly possible to situate Aristotle's analysis of the origins

of tragedy within the larger context of what Aristotle is saying prior to

this passage. Suffice it to say, he turns abruptly from a description of mankind's

"instinct for imitation (mimesis)" out of which he claims

tragedy arises, to the origin of Greek dramatic forms. After that, without

stating any reason for making the transition, he moves on to the general nature

of tragedy and comedy. In both tone and style The Poetics reads more

like lecture notes than a polished critical thesis. In light of all this,

I have translated the text with the aim of capturing both Aristotle's exact

words and also his punctuated and compressed style. If the English below makes

difficult reading, believe me, so does the Greek.]

Arising from a beginning in improvisation,

both itself (i.e. tragedy) and comedy, the former (arising) from those leading

the dithyramb, and the latter from those (leading) the phallic songs which

still even now in many of our cities remain customary, little by little it

(i.e. tragedy) grew making advances as much as was obvious for it to do, and

after having undergone many changes, tragedy came to a stop, when it attained

its own nature. Aeschylus increased the number of actors (literally, "interpreters"

or "answerers") from one to two for the first time and he reduced

the chorus' business and prepared the dialogue to take prominence. Sophocles

(introduced?—there is no verb here) three (i.e. actors) and scene-painting.

And also the grandeur (or "length," i.e. of tragedy; was increased?

by Aeschylus? Sophocles?—again, no verb!). From slight (or "short"

) stories and joking expression, since it evolved out of satyric forms, it

became reverent (only) rather late, and the meter changed from tetrameter

(i.e. comical, fast-paced) to iambic (i.e. normal, conversational). At first

they used tetrameter since drama was satyric and more dance-related, but with

the rise of speech (i.e. as opposed to "song") the nature (i.e.

of tragedy) on its own found its proper meter. Indeed, the most conversational

of meters are iambics. The evidence of this, we speak iambs (i.e. daDUM daDUM)

most of all in conversation with one another; (we speak) hexameters (i.e.

the meter of epic, DUMdada DUMdada), on the other hand, infrequently and when

we depart from a conversational tone. And also the number of episodes (or

"acts" ; was increased? –no verb). And as to the other matters,

as each is said to have been set in order, let that be said by us. For it

would be perhaps a great task to explain each thing individually.

Consider the comments of the classicist D.W. Lucas on Aristotle's views of early Greek drama. (note)

Finally, it is worth observing that Aristotle's account

of the origin of tragedy from a basically ludicrous form fits so badly with

the scheme of development presented in the first part of the chapter that

he would not have been likely to offer it unless he had been reasonably confident

that it was true. Here again it is important that he knew more than we do

about the early satyr play.

But

did he? Lucas raises a central question faced by all who encounter Aristotle's

conclusions here: "How much better was his information than ours?"

Aristotle clearly had a few advantages we do not. He lived much closer

in time to early Greek drama than we do and, to judge from the dramas he cites

and quotes, had access to fifth-century (classical) plays we do not. Furthermore,

he spent at least some of his life in ancient Athens and was personally involved

in Athenian culture. Whether or not he did, he certainly could have

gone to the ancient theatre, so he speaks from at least the assumption of having

seen Greek tragedy in action in its day, something far beyond our grasp.

But

did he? Lucas raises a central question faced by all who encounter Aristotle's

conclusions here: "How much better was his information than ours?"

Aristotle clearly had a few advantages we do not. He lived much closer

in time to early Greek drama than we do and, to judge from the dramas he cites

and quotes, had access to fifth-century (classical) plays we do not. Furthermore,

he spent at least some of his life in ancient Athens and was personally involved

in Athenian culture. Whether or not he did, he certainly could have

gone to the ancient theatre, so he speaks from at least the assumption of having

seen Greek tragedy in action in its day, something far beyond our grasp.

While these do, in fact, seem like overwhelming advantages, on close inspection

none are so imposing that we cannot question his thesis. Aristotle lived from

384 to 322 BCE, which is about two hundred years after the period he is discussing.

If that does not seem like a long time, especially in the great sweep of history,

one should remember how long two centuries can be. By our standards that is

like going back to the early days of the United States. How much would a person

today be able to remember about that period without historical records to go

on? Credible oral histories rarely exist at such a remove. So it is fair to

assume Aristotle is dependent on what data he can collect from that period or,

to put it another way, The Poetics is by definition secondary

evidence—not primary!—about

early Greek theatre.

Nor does it help those who would defend him

as an authority on primordial Hellenic drama that in all of The Poetics

he does not quote from one piece of primary historical evidence written in the

sixth century BCE: no playwright's work, no dramatic commentary, no record of

audience reactions, nothing! He either did not have access to such information

or chose not to reference his sources in The Poetics. If he did

have access to data about early drama, it seems likely a researcher who is otherwise

so meticulous would have explored those avenues and included them in his finished

work. The greater likelihood is that all but no records of early drama had survived

to his day.

To see that more clearly, it may help to think of this situation in modern terms.

For instance, in several centuries or more from now there will probably no longer

exist comprehensive records of the very earliest phases of film-making, such as Edison,

D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. De Mille's first silent version of The Ten Commandments.

(note) How will scholars in this future

age piece together the origins of that all-important watershed in art, the invention

of the movie? In the absence of clear data, will they be able to see its dependence

on theatre, the novel, opera and artistic movements like impressionism? So,

any way you look at it, Aristotle's primacy as a researcher of early

Greek theatre is not as great an advantage as it might appear at first.

Nor is his cultural advantage as great as it might look on the surface. The

Athens he knew was very different from that into which drama was born. Between

the days of early tragedy and Aristotle's lifetime, the Classical Age had come

and gone, leaving in its wake a very changed civilization and view on life.

Aristotle, without doubt, was acculturated to see the world through eyes quite

different from those which had directed and witnessed the birth of Greek drama.

Moreover, lacking immediate experience with the full cultural framework of

the time in which drama first came to light, he was as prone as anyone to make

misassessments about the inclinations and motivations of his remote ancestors

in the Pre-Classical Age. Granted, even if faulty, his reconstructions of the

past probably appeared sensible to him and his peers—and perhaps to many

today, too—nevertheless, his conclusions will have diminished validity

if they do not address directly the age in question. In other words, Aristotle

was at some risk of making the same mistake all historians are: his conclusions

possibly say more about himself and his own times than the subject he is studying.

D. Conclusion: How right is Aristotle about the origin of

tragedy?

With all that in mind, let us examine Aristotle's hypothesis about the origin

of Greek drama. In essence, Aristotle looked at theatre-like entertainments

and ritual celebrations that were not tragedy as such and that had survived

to his day and seemed "primitive" to him. Recall his words:

"which still even now in many of our cities remain customary." From that he concluded that these celebrations must somehow have played a direct role in

the evolution of tragedy. The postulates underlying The Poetics—that

is, Aristotle's assumptions about what constitutes historical data in the case

of early theatre and how it should be ordered—are remarkably similar to

those adopted by Frazer in The

Golden Bough. When he sees something that looks primitive to him, he assumes it must also be aboriginal.

And that opens Aristotle up to the same criticisms as those which have been

directed at Frazer. Basically, Aristotle concludes that primitive ritual in some form led to

theatre following a timeline of inevitable "progress" toward more complex

forms: "[tragedy] grew making advances as much as was obvious for it to

do, and after having undergone many changes, tragedy came to a stop, when it

attained its own nature." But who's to decide what is "obvious"

or "its own nature"? Without a clear and documented basis in data,

such assumptions cannot carry much weight.

The

dithyramb, what Aristotle cites as the art form from which

tragedy arose, also poses several obstacles to the construction of a coherent

case for some sort of linear development in the performing arts of early Greece.

To begin with, no early dithyrambs survive from antiquity. Indeed, until recently

we did not have any dithyrambs at all. However, in the last century a few

have emerged from the sands of Egypt. Unfortunately for our purposes here, they

are later dithyrambs by a classical—not pre-classical!—poet

named Bacchylides, and their connection to the earlier dithyrambs

about which Aristotle speaks is unclear (see

Reading #1). It is enough to note that Bacchylides' dithyrambs do employ only sung language, nothing even close to spoken language, nor do they entail

elaborate characterization, as tragedy usually does. That means it is questionable

even whether dithyrambs represented institutional theatre in any conventional sense—as opposed to more music-based artforms like opera or ballet—much less served

as the predecessor of tragedy.

The

dithyramb, what Aristotle cites as the art form from which

tragedy arose, also poses several obstacles to the construction of a coherent

case for some sort of linear development in the performing arts of early Greece.

To begin with, no early dithyrambs survive from antiquity. Indeed, until recently

we did not have any dithyrambs at all. However, in the last century a few

have emerged from the sands of Egypt. Unfortunately for our purposes here, they

are later dithyrambs by a classical—not pre-classical!—poet

named Bacchylides, and their connection to the earlier dithyrambs

about which Aristotle speaks is unclear (see

Reading #1). It is enough to note that Bacchylides' dithyrambs do employ only sung language, nothing even close to spoken language, nor do they entail

elaborate characterization, as tragedy usually does. That means it is questionable

even whether dithyrambs represented institutional theatre in any conventional sense—as opposed to more music-based artforms like opera or ballet—much less served

as the predecessor of tragedy.

Indeed, one of Bacchylides' dithyrambs includes

only a single character, while another has no characters at all, only a chorus,

something unheard of in extant tragedy. Moreover, these dithyrambs are episodic,

meaning they do not have conventional plots with a clear beginning, middle and

end, again unlike all known Greek tragedies. What they seem to be are short

"epics" cast in the form of lyric poems to be performed by a chorus, effected through poetic and elevated language that focuses on the genealogies and epithets

of heroes and peopled by huge and lofty characters, mostly gods and

heroes, not the desperate, stricken mortals who dominate the tragedies available

to us. (note)

In sum, none of this adds up to a compelling case, at least superficially,

for dithyramb as the precursor of tragedy—put simply, the dithyrambs we

have do not look much like the tragedies which are extant—so is

it possible, then, that Aristotle is wrong about the origin of tragedy? Before

entertaining such a notion, we must admit that it would be foolish to cast away

lightly the opinion of one of the finest minds ever and, even if his report

constitutes secondary evidence, a researcher who stands much closer to the actual

event in question than we are. But let us assume for a moment that Aristotle

is mistaken. It is still incumbent on his prosecutors to show how and

why, and to present some better case than he does. No small task!

Suppose, then, that we had access to all the dithyrambs ever written in early

Greece and we could see for ourselves that there were, in fact, no dithyrambs

which resembled tragedy closely enough to posit a cause-and-effect relationship,

as Aristotle does. He is not an idiot or liar, so it is incumbent on us to find

some reasonable explanation for his misconstruction of the data. Fortunately,

that is not an insurmountable challenge.

The Poetics does not focus on the issue of origins with nearly the

sort of attention modern theatre historians might wish for. There is, in fact,

very little in this work about the creation of drama and, to judge from the fractured

density of Aristotle's language—if it is even his language and

not the notes of someone listening to his lectures, as some scholars suppose—he

did not revise the work to the degree typical of his other works. Thus, it seems

fair to say that the question of the origin of drama was not central in his

mind.

Now let us assume the converse, that Aristotle is correct and evidence

actually once existed that there were dithyrambs that looked like tragedies,

at least on paper. He could, after all, never have seen such dithyrambs performed

since he lived so long after the fact. Aristotle could be making

an error to which many historians of theatre are susceptible. That is, he has

assumed a connection between theatrical genres which happen to look alike in

written form—in this case, dithyrambs and tragedies both include choruses,

lyrics, characters, scenes, dramatic tension, climax and so on—but, when

seen in theatres in performance, they probably looked and were very different.

Much the same could be said for opera and oratorio, or musicals and music videos.

Perhaps, a more modern analogy will help clarify the situation. For instance,

compare the screenplays of animated films and live-action movies. They look,

in fact, very similar, but the finished products in performance are worlds apart

and, as we know, grew out of vastly different artistic milieux. All in all,

if it is true that Aristotle is projecting a hypothesis based primarily on evidence

from his own day and not the Pre-Classical Age, he shows himself to have been

a purveyor—but not necessarily a spectator—of plays who has made

a classic "reader's error." He saw what looked to him like a similarity

between different forms of performance art, when, in fact, it was actually only

a superficial "papyrus likeness," and from that he assumed there

was a direct evolutionary relationship between the genres.

It is possible to see that same sort of error

elsewhere in The Poetics. Aristotle claims—or seems

to claim since the text is gravely abbreviated—that "Sophocles (introduced?)

three (actors) and scene-painting." (note)

But it is obvious even at our remove that, if he did, Sophocles must have done

this extremely early in his career, since Aeschylus utilizes three speaking actors

in The Oresteia, a trilogy produced in 458 BCE. Sophocles' career had

begun only a decade earlier (ca. 468 BCE). How likely is it that a novice,

before even having earned his dramatic stripes, would have been allowed to reformulate

the rules in as rigidly controlled an environment as the prestigious, award-granting

religious festival of the City Dionysia? In all probability

Aristotle—if he actually wrote these strangled words—is incorrect

on this point, and the reason for this is also not altogether unfathomable.

Though

Aeschylus' later plays do, in fact, utilize three speaking actors—and

perhaps at one point even four (Libation-Bearers 900ff.)—never

at any moment is there a three-way conversation on the stage, that is, no "trialogues"

anywhere. If one were to read Aeschylus' dramas quickly, not following closely

the assignment of parts demanded by the text or carefully reconstructing the actors'

movements backstage, it would be very easy to conclude that Aeschylus never

employed more than two speaking actors in the execution of his drama. Careful

scrutiny of Aeschylus' plays, however, belies this presumption.

Though

Aeschylus' later plays do, in fact, utilize three speaking actors—and

perhaps at one point even four (Libation-Bearers 900ff.)—never

at any moment is there a three-way conversation on the stage, that is, no "trialogues"

anywhere. If one were to read Aeschylus' dramas quickly, not following closely

the assignment of parts demanded by the text or carefully reconstructing the actors'

movements backstage, it would be very easy to conclude that Aeschylus never

employed more than two speaking actors in the execution of his drama. Careful

scrutiny of Aeschylus' plays, however, belies this presumption.

For instance, in the great confrontation between

Agamemnon and his wife Clytemnestra in Aeschylus' Agamemnon, the only

characters who are given lines to speak are Agamemnon and Clytemnestra—and the chorus, of course.

Yet there is another character on stage during this scene, Cassandra, though she speaks not a word in this scene. Later, however, in another scene—and she never leaves the stage in between—she does finally talk. So, the same actor must be portraying Cassandra throughout this section of the play. (note)

It is clear, then, Aeschylus' Agamemnon does, in fact, demand three

speaking characters, though a cursory glance at the text would seem to indicate

not. In sum, the case is strong that Aristotle has made a "reader's error"—if,

in fact, he wrote the words "Sophocles three" and in saying this meant

that the tragedian had introduced the third actor—and has assumed from

a cursory overview of Aeschylus' drama what the playwright's scripts called

for in terms of performers. That is, Aristotle did not fully envision the requirements

of theatrical production in Aeschylus' day. It would accord well with the complete

neglect in The Poetics of any discussion regarding rehearsal and the physical dimension of

stage productions.

All this casts Aristotle's assessment of early theatre in, at best, a mottled

light. This type of misconstruction suggests he did not make any serious effort to seek out the theatre

recoverable in the scripts he surveyed. In other words, he reads and perhaps listens to drama

in the "playhouse of his mind," but he does not watch it as carefully

as the theatre demands, which makes him liable to certain types of critical

errors. In the words of Ibn Khaldun, he shows an

"inability rightly to place an event in its real

context, owing to the obscurity and complexity of the situation. The chronicler

contents himself with reporting the event as he saw it,..."—in this case, in his mind—" thus distorting its

significance."

If so, it opens the possibility of consigning Aristotle's theory linking early

tragedy with dithyramb to the same family of oversights as his purported attribution

of the third (actor) to Sophocles. To wit, the philosopher saw apparent similarities

in the written texts of dithyramb and tragedy and from that assumed some sort

of evolutionary connection—it is not an illogical conclusion by a "reader's"

standards since these texts would have looked alike in written form—nevertheless,

the graphic similarity may not have an equivalent validity in the theatre of

pre-classical Athens. Or, to put it another way, Aristotle is a "lumper"

who postulates a direct line of development in the data by linking together

forms he knows to have existed early on. The fact is, the data—what

few there are!—leave much room to play the "splitter," too.

That opens the door to supposing that dithyramb was not the "father"

of tragedy, but a similar-looking form of entertainment that grew from the same

stalk of the "family tree" as tragedy did. In other words, dithyramb

was not necessarily a direct ancestor of tragedy or even a close relative, but

rather a sibling or cousin of some sort. All in all, the standard view of the

origin of Greek drama in the Pre-Classical Age—whether we orchestrate

our hypotheses around Aristotle, Thespis or goats—is hardly unassailable.

It is limited at best, and a real possibility exists that all three purported data points are simply wrong.

II. Those Few Known Facts about Early Greek Drama

In such a situation, it is wise to step back and re-assess what we know. What

are the facts about early Greek drama, where is there room to speculate and what

limitations should there be to our speculation? This much at least is certain:

• Greek theatre must have arisen in the early or mid-500's BCE, because

drama is simply not mentioned in texts or credible sources prior to that time.

• By 534 BCE theatre is clearly underway because that was when Pisistratus,

the tyrant of Athens, inaugurated the urban ceremonies honoring the god Dionysus,

a festival that for the first time in recorded history included theatrical

performances. Thus, all reasonable evidence suggests that Athens was the cradle,

if not the birthplace, of early drama.

• That innovative festival, called the City Dionysia,

is certainly worth examining in detail, because from what is known about

its general mood and structure it may be possible to speculate constructively

about Pisistratus' reasons for making drama part of this festival.

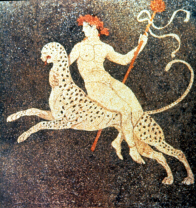

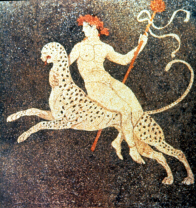

• Crucial, too, in all this is Dionysus, a god seen by the Greeks as

a foreign import. His worship was said to have originated in Asia Minor (modern

Turkey) and to have entailed several non-Greek elements, such as "orgiastic"

rituals.

So, amidst all the conflicting and confusing data, there do exist at least

some things we can rely on. If these data do not form a seamless bridge

to the truth, they are at least stepping stones on which to cross a very treacherous

torrent of conflicting information. Let us begin, then, by investigating the worship of Dionysus because it may shed light on the nature of early theatre and, perhaps, even help sort out the evidence.

The alien nature of Dionysiac worship is reported to have precipitated more

than one crisis in Greek society. As many today would also, the ancient Greeks

initially distrusted any social force that preached release of inhibitions,

promotion of the downtrodden in society—and women, in particular, clearly

one audience at whom the cult was directed—and general dancing, drinking

and cavorting. (note)The form of worship sanctioned in Dionysian religion was ecstasy, literally "the act of standing outside oneself." At the highest pitch of the celebration, it was believed that worshipers left themselves, as the god entered their bodies, and they could then perform miracles and wondrous acts beyond normal human capabilities. That the "impersonation" of a human by the god bears some resemblance to what an actor does in performing a drama has led many a scholar to assert an evolutionary connection between this sort of worship and the performance of drama. For this and other reasons, Bieber asserts: "The religion of Dionysus is the only one in antiquity in which dramatic plays would have developed." (note)

The alien nature of Dionysiac worship is reported to have precipitated more

than one crisis in Greek society. As many today would also, the ancient Greeks

initially distrusted any social force that preached release of inhibitions,

promotion of the downtrodden in society—and women, in particular, clearly

one audience at whom the cult was directed—and general dancing, drinking

and cavorting. (note)The form of worship sanctioned in Dionysian religion was ecstasy, literally "the act of standing outside oneself." At the highest pitch of the celebration, it was believed that worshipers left themselves, as the god entered their bodies, and they could then perform miracles and wondrous acts beyond normal human capabilities. That the "impersonation" of a human by the god bears some resemblance to what an actor does in performing a drama has led many a scholar to assert an evolutionary connection between this sort of worship and the performance of drama. For this and other reasons, Bieber asserts: "The religion of Dionysus is the only one in antiquity in which dramatic plays would have developed." (note)

There is much to applaud in Bieber's approach. To begin with, the festivals of Dionysus regularly included dance, and at the same time the impersonation of deities, the use of masks and parades of celebrants who can be seen to resemble tragic choristers. Besides its innate theatricality, Dionysian religion was also a later import to Greece and thus, unlike better established cults with age-old rituals, it was open to new formulations in its worship, celebrations that might involve all sorts of "entertainment" (epic narration, lyric singing, choruses, and so on). Furthermore, the story of Dionysus as told in myth is varied and full of different events, indeed a rich storehouse of different-looking episodes that would make a fine arena for theatre, if a playwright were inclined to dramatize them. In sum, looking on the surface of things, one is forced to agree with Bieber that Dionysus' world in early Greece seems like the perfect womb for fetal drama. Now all that's needed is strong evidence corroborating that was what actually happened.

Unfortunately, for all the sense Bieber's argument makes to many today, the

corroborating evidence that what she proposes did, in fact, take place is simply

not there. Moreover, when one looks below the surface, there are powerful counterarguments

to the thesis that drama arose directly or smoothly from Dionysiac cult practices.

While the rituals attested as Dionysian are indeed theatrical, they are not

by any means institutional or autonomous theatre. Yes, there is impersonation,

which assumes that there are also watchers and watched, but the nature of the

words spoken in these performances is unknown. If the scripts of these ceremonies

did not vary but comprised basically the same hymnic praise of the god year

after year, it is less like a play than an Easter mass, which is certainly dramatic

but not drama as such. Finally, for all the possibilities of creating new and

innovative scripts which the mythic sagas of Dionysus inherently contained,

there is little evidence that such play-texts were ever created in classical

drama. It's a fine suggestion but things just don't seem to have played out that way

in antiquity.

And

there is another problem. A well-known Athenian maxim from the day claimed that

Greek tragedy had "Nothing to do with Dionysus."

This popular saying dates back to at least the Classical Age, where it appears

to have been assumed, as a joke almost, that, although tragic drama was performed

at the Dionysia in honor of its eponymous deity, the plays rarely revolved around

Dionysus or his worship explicitly, which is something we can see for ourselves.

All but one of the thirty-three preserved classical tragedies deal with myths

that do not center around Dionysus. The question, then, is not about the validity

of this adage, but how far back in time it applies. Does the tendency well-evidenced

in the Classical Age not to perform plays about Dionysus at the Dionysia

go back into the Pre-Classical Age, perhaps even to the origin of drama itself?

And

there is another problem. A well-known Athenian maxim from the day claimed that

Greek tragedy had "Nothing to do with Dionysus."

This popular saying dates back to at least the Classical Age, where it appears

to have been assumed, as a joke almost, that, although tragic drama was performed

at the Dionysia in honor of its eponymous deity, the plays rarely revolved around

Dionysus or his worship explicitly, which is something we can see for ourselves.

All but one of the thirty-three preserved classical tragedies deal with myths

that do not center around Dionysus. The question, then, is not about the validity

of this adage, but how far back in time it applies. Does the tendency well-evidenced

in the Classical Age not to perform plays about Dionysus at the Dionysia

go back into the Pre-Classical Age, perhaps even to the origin of drama itself?

That, in turn, brings up another problem, the very different modes in which

Dionysiac ritual, based as it is on ecstatic revelry, and tragedy are conducted.

Almost all the tragedies we have access to are fairly serious in tone, many

very serious. If tragedy arose from the riotous, grape-stomping, orgiastic

rituals of Dionysus worship, how and when and why did this total about-face

in tone and attitude take place? The result of these questions is that for all

its apparent validity the quick-and-easy association of Dionysiac ritual and

early tragedy is much more problematical than it may seem at first glance, yet

another lesson in the dangers of applying what to us makes sense to a past culture

that had sensibilities very different from our own.

III. Modern Theories about the Origin of Greek Drama: Murray

and Else

Given that, theatre historians must seriously

consider the possibility that tragedy did not naturally grow out of Dionysiac

ritual but was somehow layered onto it. Indeed in the twentieth century, three important theories were proposed building upon that premise: Murray's suggestions surrounding the

"year-spirit," Ridgeway's "Tomb Theory," and Else's proposal

that Greek drama is the product of Thespis' and Aeschylus' genius. Let us review

them now.

A. Murray, Cornford and the Eniautos Daimon

First, Gilbert Murray, and later F.M. Cornford, posited that drama evolved

out of a celebration of the year-spirit—in Greek, eniautos

daimon ("annual spirit")—a ritual tied to the changing

of seasons. (note) In Murray's view, comedy

began as a celebration of the marriage of gods and the fertility that results

of their happy union; conversely, tragedy originally mourned some god's death

and usually took place in autumn. Much of this work built upon Frazer's theories

with all their concomitant biases and positivistic fallacies. When that attitude

came under fire, Murray's theoretical infrastructure also began to crumble.

From another quarter, critics of Murray's work pointed out that, while the

term eniautos daimon is attested, there is remarkably little evidence for the celebration of a year-spirit in Greece. On top of that, the evidence for such celebrations

does not, at least on the surface, suggest that they closely resembles later classical tragedy, at least as we know it. And to cap things off, Greek tragedy was regularly celebrated in early spring, just

as the year was renewing itself—the wrong time of year, to judge by seasonal

change—and comedy was performed at the same festival. According to many

scholars, the congruence of diametrically opposed rituals according to the year-spirit's

religious calendar was a fatal blow to this theory. Except for stopping a show

here and there, the weather just doesn't seem to have played a big part in Greek

theatre.

B. Ridgeway and the Tomb Theory

Along similar lines emerged a second theory, one rooted in very different set of data. This thesis sets out to explain why tragedy had "nothing to do with Dionysus."

This proposition begins with a passage in Herodotus' Histories which

offers, if rather succinctly, another possible avenue for the distillation of

drama out of non-Dionysian ritual:

Herodotus, The Histories, Book 5.67.4-5 [Herodotus is discussing

the rise of Athenian democracy which he sees as the fallout of a conflict

between two men, Cleisthenes and Isagoras. In reporting about the former,

he digresses into a discussion of Cleisthenes' grandfather, also named Cleisthenes.

This older Cleisthenes had tried, according to Herodotus, to rid Sicyon, a

city in southern Greece, of the worship of the hero Adrastus and impose on

it that of a hero imported from Thebes, Melanippus. Adrastus had lived much

earlier (in mythological times) and later his spirit was seen to protect the

city. Thus, the Sicyonians worshiped Adrastus as a demigod and performed certain

rituals in his behalf, which Herodotus now describes.]

But the Sicyonians by tradition very excessively worshiped

Adrastus, the reason being that the country (i.e. Sicyon) was once Polybus'

very own and Adrastus was Polybus' maternal grandson, but childless at the

time of his death Polybus gave to Adrastus the realm. So, in other respects

the Sicyonians used to honor Adrastus but particularly with respect to his

sufferings (or "experiences" ) they held celebrations with tragic

choruses, honoring not Dionysus but Adrastus. Cleisthenes (i.e. the older)

returned (or "delivered over" ) the choruses to Dionysus and the

other sacrifices to Melanippus.

This has led some scholars, foremost among

them William Ridgeway, to propose the theory that this sort

of hero-worship was the font from which Greek tragedy came, in Ridgeway's words:

(note)

Tragedy proper did not arise in the worship of the Thracian

god Dionysus; but sprang out of the indigenous worship of the dead . . . the

cult of Dionysus was not indigenous in Sicyon but had been introduced there

. . . and had been superimposed upon the cult of the old king; . . . even

if it were true that Tragedy proper arose out of the worship of Dionysus,

it would no less have originated in the worship of the dead since Dionysus

was regarded by the Greeks as a hero (i.e. a man turned into a saint) as well

as a god.

This theory, called the "tomb theory" or "hero-cult

theory," has certain advantages over the supposition that tragedy

arose from Dionysian worship. Principally, it directly addresses the content

and form of all later, extant classical tragic dramas which invariably include

choruses, most often focus on human heroes over immortals, and frequently center

around their mortality. The performance of a hero's life at his "tomb,"

presumably a narrative recreation of his life and death accompanied by a chorus,

does indeed bear a strong, if superficial, resemblance to later tragedy.

But there are serious drawbacks to the "tomb theory." Primarily,

this evidence is so scant that, if the theory is correct, the discussion about

the origin of Greek tragedy is over. This leaves nothing else to say, for there

is no other information about these Sicyonian rituals to be found in the historical record.

Herodotus' account constitutes our one and only source of information about this

custom. No other historian, no later commentator, no vase painting, nothing

else in antiquity refers to this sort of entertainment, as far as we know.

Close attention to Herodotus' language also raises some serious issues about

the validity of this perspective. The historian appears to be pushing the very

same point as Ridgeway, that tragedy arose from these sorts of celebrations

("the Sicyonians . . . held celebrations with tragic choruses, ..."

). To call them "tragic" choruses is essentially to retroject a later

cultural term onto an earlier custom and begs the point that these songs in

some way constitute "proto-tragedy." Note also that Herodotus seems

to be denouncing the cult of Dionysus as the font of tragedy when he says "honoring

not Dionysus but Adrastus." The great "Father of History" looks

to be asserting the same argument as Ridgeway and his modern followers.

In other words, he does not just happen to record for us the true origin

of drama, but is making the very point on very slender evidence. If so, and

if he'd had more data to this effect, Herodotus would surely have cited it.

But he does not, and that speaks poorly for the credibility of this thesis.

All in all, given the scarcity of information here and Herodotus' potential

bias, we must take the "tomb theory" with a grain of salt, if not

a whole shaker. After all, when the facts lead to a dead end, we're at "Thespis"

all over again.

C. Else's Theory

Speaking of Thespis, a third theory also downplays

the role of Dionysian worship in the formation of early Greek drama and has

won generally wider support. Gerald Else, a twentieth-century

classicist, suggested looking at drama, not as the product of some other type

of ritual or celebration nor even the evolution of older forms into something

new and different, but as a unique event without true forebears. Else calls

Greek drama "the product of two successive creative acts by two men of

genius," meaning Thespis and Aeschylus. (note)

In other words, tragedy simply "happened" because two men in fairly

close succession saw possibilities in the art form, and in the process of reshaping

it they created drama, almost incidentally.

Else's theory has several clear advantages over the others. First and foremost,

it explains the chronology and locality of tragedy's genesis. There can be little

doubt that it happened in Athens at some point during the sixth century BCE.

Even if there are theatre-like entertainments elsewhere in the Greek world or anywhere prior

to the rise of tragedy, there is no competent ancient source that does not recognize the

Athenians in some way as the inventors of drama, and there is not even a shred

of credible evidence to suggest otherwise. So to Else, the dynamic combination

of Thespis and Aeschylus, not some poorly attested social institution or vague seasonal celebration, was the

real force behind the drive to create this art form. In Else's eyes, tragedy is the unique concoction

of men who lived at the right moment in the right place to bring theatre to

life.

The form and content of tragedy, then, do not matter in the same way they do

if we suppose that tragedy is an elaboration of certain pre-existing celebrations or rituals.

What tragedy became is simply what Thespis and Aeschylus saw as practicable

entertainment, because in manufacturing the artform, they simply used what they

wanted to of the culture and arts around them. If tragedy looks like it

has pieces of Dionysiac ritual or hero-worship or lyric poetry or epic, it is

because that is what Thespis and Aeschylus selected at will and from these elements

forged drama. It must also have been to some extent what their public wanted,

in the language of modern advertising, what "sold."

Essentially, what Else is doing is subverting the whole mentality of "evolution,"

the sense that art entails cause and effect which over time lead to visible

changes in its presentation. Instead, he has posited a theory of spontaneous

generation for tragedy—a student of mine aptly called this the "creationist

theory" of Greek drama—inasmuch as Else is essentially saying that

early Greek theatre did not evolve, but was "created," born several

times, in fact: in Thespis' early touring shows, and again in 534 BCE when Pisistratus

instituted the City Dionysia in Athens and decided to include drama among its

celebrations, and finally in Aeschylus' masterful hands during the early Classical

Age when it took on the shape in which we know it. It's hard to argue against

Else's contentions, and thus many scholars today follow his thesis.

But, like all the others, his theory is not without its drawbacks. It leaves

little room for universal application, because it applies by definition only

to Athens in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE. In premise, Else's thesis cannot

be expanded to include China or India, where we know theatre also developed.

There is no room for a common human element when one sees Greek drama as "unique."

While this may be true, one should hope it is not, because, just as with Ridgeway's

Herodotus-based theory, the argument would be at a dead end.

To many scholars, that alone is unsatisfying. Furthermore, although there is

much to question in Aristotle's thesis, classicists and theatre historians are—and should be!—ill at ease throwing

the great philosopher's notions out the window altogether, even if there seem

to be good reasons for doing so. All in all, it would be much more satisfying

if we could incorporate Aristotle's ideas in some form at least. And finally,

to say that in the end "geniuses invented drama" seems somewhat obvious.

As another student of mine once blurted out in class when I was outlining Else's

thesis, "Well, duh!" Unfortunately, I must concur.

D. Conclusion

In sum, the facts about early Greek theatre appear to lead to shaky or unsatisfying

theories at best, and the whole situation looks lamentable. Facing a seemingly

insoluble problem, we should probably throw up our hands and surrender, especially

given the underwhelming body of evidence we can bring into play. With little

hope of uncovering more data—remember that Aristotle seems to have had

not much more to go on than we do, and if he didn't, is there any reasonable

expectation we ever will?—the gavel should probably come down

on this mistrial and we should all leave the courthouse. Unless, of course,

the reason there isn't better evidence is not because important data have failed

to survive but because the evolution of drama did not take place the way any

of these theories suggest.

In other words, perhaps we lie at the heart of the problem. Perhaps

we are expecting to find something that is not there and never was,

or there was so little of it that none is likely to have survived the

ravages of time. To put it another way, perhaps we are looking for a preponderance

of data that never existed. In that rests the only real hope of finding credible

answers about early Greek drama, especially in light of the grave improbability

that we will stumble across new data about the events surrounding the origin

of Greek drama. Perhaps we already have all the evidence we need and all we

need to do is to recognize it as such. To be continued.

Terms, Places, People and Things to Know

|

Thespis [THESS-piss]

Tragoidia [trah-GOY-dee-uh]

Aristotle

The Poetics

Dithyramb [DITH-ur-ram]

Bacchylides [back-KILL-uh-dees]

Trialogue(s)

Dionysus [die-oh-NICE-suss]

|

City Dionysia [die-oh-NISS-se-uh]

Ecstasy

"Nothing To Do With Dionysus"

Year-Spirit

William Ridgeway

Tomb-Theory

Hero-Cult Theory

Gerald Else |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

First,

except for what we are told concerning the origin of drama, Thespis

is entirely unknown, a name that means essentially nothing to us except as the

purported founding father of Greek drama. Worse yet, all sources that talk

about him are late, none even vaguely contemporary. For instance, our information

about his cart comes primarily from Horace, a Roman poet who wrote more than

half a millennium after the age when Thespis would have lived. Moreover,

that very few earlier sources mention him is particularly troubling if indeed

we are to ascribe to him the invention of tragedy.

First,

except for what we are told concerning the origin of drama, Thespis

is entirely unknown, a name that means essentially nothing to us except as the

purported founding father of Greek drama. Worse yet, all sources that talk

about him are late, none even vaguely contemporary. For instance, our information

about his cart comes primarily from Horace, a Roman poet who wrote more than

half a millennium after the age when Thespis would have lived. Moreover,

that very few earlier sources mention him is particularly troubling if indeed

we are to ascribe to him the invention of tragedy.