Leading in Water: Mahmoud Ali

Mahmoud Ali, an undergraduate student at Zagazig University in Egypt, was given a unique opportunity: to travel halfway across the world to study at Utah State University.

From the Fall 2019 Edition of Discovery

What do humans need to survive? Air, water, nutrients, shelter, sleep? At first glance, it’s a short and, seemingly, simple list. Yet, ensuring all of these needs are met becomes increasingly complex at closer observation.

What if the air and water are contaminated or scarce? What if nutrients are in short supply or the person needs assistance to take them in? What if a natural disaster makes shelter, and sleep, impossible?

Robinson addresses attendees of the Berlin ISS. Symposium 2012 in Germany. Theme of the gathering was “Research in Space for the Benefit of Humankind.”

Now, ask these questions again away from the familiar comfort of planet Earth. How do you sustain human life in space? On other planets?

Those are questions USU alumna Julie Robinson (BS’89, Chemistry and Biology), as Chief Scientist of the International Space Station (ISS) at NASA Headquarters, contemplates on a daily basis.

Such challenges may seem insurmountable but Robinson, who joined NASA as a civil servant at Houston’s Johnson Space Center in 2004 and became Deputy ISS Program Scientist in 2006, followed by ISS Chief Scientist a year later, has long been a leader in the space agency’s interdisciplinary process. She’s grabbed the reins to prioritize countless research ideas and distill an integrated approach from concept to design and assembly and use.

It’s not a rapid process, but a step-by-step journey.

“Science is a way of knowing that begins with observations, continues with identifying alternate hypotheses and testing them with well-designed experiments,” says Robinson, who is currently based in the Washington, D.C. area, says. “At its pinnacle, the process generates a natural law.”

Engineering, she says, extends that way of knowing one step further to use the knowledge gained and apply it to something new. In simplest terms, scientists are focused on understanding the problem, while engineers are focused on designing the solution.

“But I can tell you from my career at NASA that the two slightly different views of the end goal are so synergistic that neither can advance without the other,” Robinson says. “Together, we’re driven by a passion for knowing ‘how’ and ‘why’ in the universe.”

That passion, she says, is what will drive advancements in human space travel, and allow people to explore and thrive beyond the confines of our island planet. The journey will advance step by precarious step and will include steps back, stumbles and dead ends.

"It's not an easy path," says Robinson, who was awarded the NASA Outstanding Leadership Medal in 2011. "But the ISS gives us a stepping stone to living and working in space, then Artemis lets us live and work on the moon, and then we are ready to go on to Mars."

Robinson’s own, personal path is marked by some challenges and unexpected detours.

While a senior in high school, her parents sat her down to deliver some discouraging news.

“We don’t have the money to send you to college next year,” they told her.

“Money was tight,” says the Pocatello, Idaho native, who graduated from southeast Idaho’s Highland High School in 1985. “They suggested I might have to work full-time for a year or so, to fund my studies.”

Robinson was disappointed, but still hopeful, as she adjusted her plans.

“Then, out of the blue, I got a call from Utah State,” she says. “The university offered me a Presidential Scholarship – a full-tuition, four-year scholarship. It was an answer to a prayer.”

Robinson notes this was before the Internet and USU had no website advising students of scholarship opportunities.

“Things weren’t as transparent as they are now,” she says. “I’m happy to see the university continues to award these scholarships. But, at the time, I had no idea they existed, or that I was being considered.”

Bolstered by the unexpected financial support, Robinson headed to Logan to begin her studies. She chose chemistry as her major and subsequently added biology as a second major.

“The combination of the two disciplines was perfect for me,” she says. “It was interesting to work at the intersections of biological and physical science.”

She found a welcome home in USU’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, which she says was small enough to afford her one-on-one attention from faculty.

“I especially remember my organic chemistry class with Professor Grant Gill Smith (1921-2010),” she says. “I was one of only two women in the class and he insisted we sit at a station close to him, because ‘women need more assistance.’ I tell women that story today and they are shocked to know that we put up with things like that. We thought it was funny.”

The Honors student quickly proved her mettle, consistently performing at the top of a very competitive class.

“Dr. Smith invited me to work in his lab and he became a valuable mentor, teaching me about crossing different disciplines as you see research opportunities,” she says.

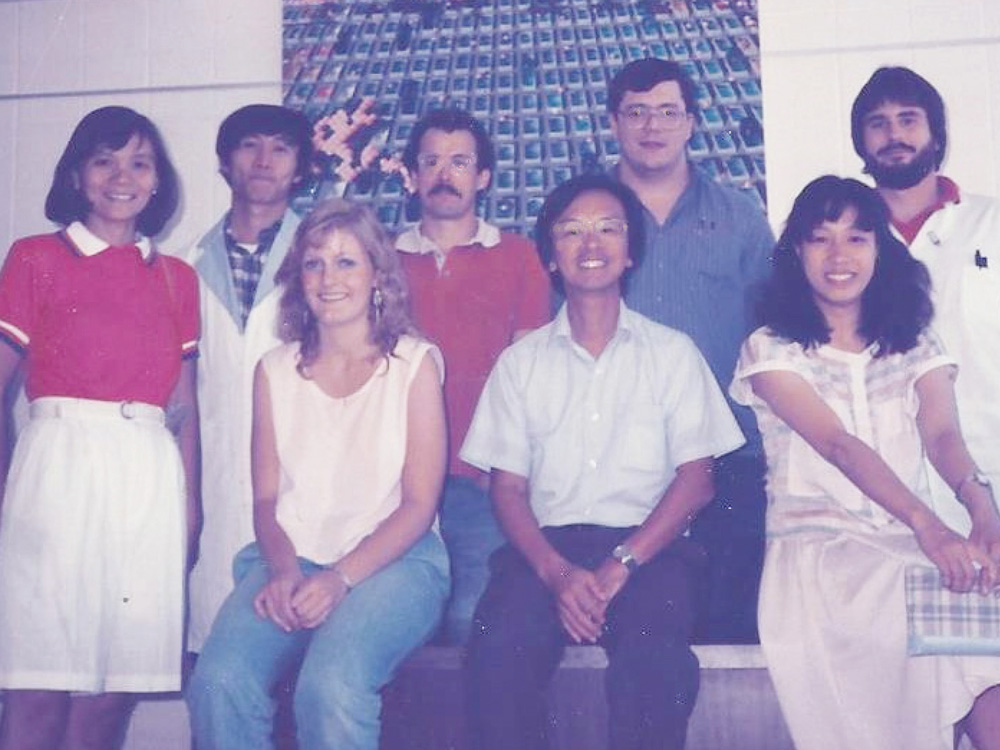

During her undergrad years, Robinson also worked in the lab of Biology Professor Joseph K.-K. Li (1940-2015), who taught her how to culture cells and perform DNA sequencing.

“In those days, we sequenced DNA in hand-poured gels,” she says. “It was very labor-intensive, and could take a grad student four years to sequence a single virus.”

But the hard work paid off.

“I used my understanding of those disciplines later in making recommendations to develop new cell culture and DNA sequencing facilities for the ISS,” Robinson says.

Li also proved a critical role model for the aspiring scientist.

Dr. Li ran the lab like a family, with grad students helping the undergrads,” she says. “But he always had a bench available to demonstrate how to do things himself. When I left his lab to go to work at another, I made sure to recommend a great student to replace me, because it was such an outstanding opportunity to work in the group.”

Other influential mentors were Professors Joseph Morse, then director of USU’s Honors Program, and Karen Morse, USU’s first woman Science dean and President Emerita of Western Washington University.

“They taught me I could be broad in my educational focus,” Robinson says. “Though both consummate scientists, they instilled in me that humanities were just as important as the sciences.”

Her 1989 Honors capstone thesis, “Moral Development Theories: Controversy, Bias and a New Perspective,” dealt with intricacies of philosophy, not chemistry or biology, as Robinson explored “moral taxonomy,” comparing moral development from a number of approaches.

Despite an outstanding undergraduate career, Robinson had doubts about pursuing graduate study.

“I wondered if I should set my sights a little lower and just find a job,” she says. “I hadn’t had a lot of women role models and my confidence was lagging.”

Joe Morse wasn’t having it, Robinson says.

“He looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘If you don’t go to grad school and get a Ph.D., this world will really miss out,’” she says.

It was the boost Robinson needed. Years later, after earning a doctoral degree in Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology in 1996 from the University of Nevada, Reno, she wrote to Joe.

“I told him his words of encouragement had changed my life,” she says.

Robinson headed to the University of Houston for postdoctoral research. Using skills she gained in earth remote sensing at UNR, Robinson created maps showing how varied wetland species along the Texas Gulf Coast were responding to hurricanes.

An unexpected turn developed into a surprise opportunity, she says, when NASA scientists invited Robinson to develop Earth science training for astronauts going to the Mir space station. Mir, operated by the former Soviet Union and later, Russia, was the first modular space station. As she initiated the project, Robinson joined Lockheed Martin in the Image Science Laboratory at Houston’s Johnson Space Center.

“In addition to training astronauts, I led a major, NASA-sponsored scientific project to facilitate a distribution network for global maps of coral reefs in the developing world,” Robinson says. “I collaborated with fellow ecologists and conservation biologists to increase access and use of NASA data and in the publication of a remote sensing textbook.”

From Lockheed Martin, she joined NASA, which welcomed her broad science expertise.

“A lot of people focus on NASA’s prowess in aerospace engineering, but we have a broad scientific mission, including study of the global Earth system and understanding the impacts of extreme hazards of space on human health,” Robinson says. “I’ve never taken a single class in science that I haven’t used.”

“We do everything on the ISS,” she says. “We need people from many backgrounds, experiences and disciplines.”

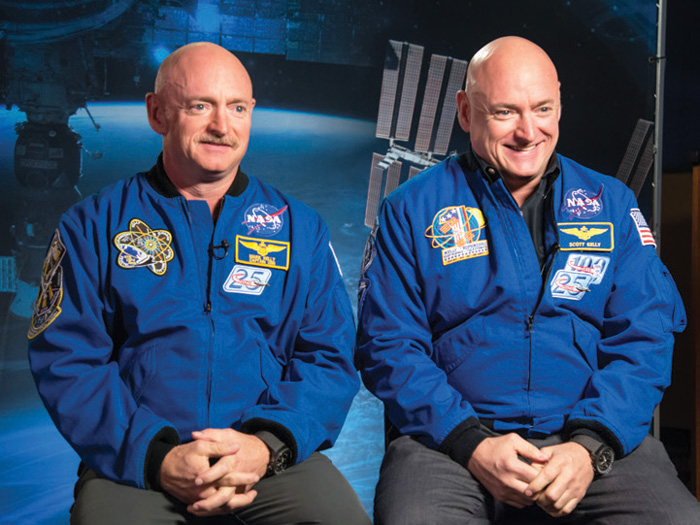

Among the many fascinating projects in which Robinson has been involved includes NASA’s landmark Twins Study, featuring identical twin astronauts Scott and Mark Kelly. Scott Kelly spent a year in space, from March 2015 to March 2016, while Mark Kelly stayed on Earth as a control subject.

Collected data afforded scientists the opportunity to observe the effects of space travel on the human body.

“It was extraordinary being in conversation with Scott, when the idea for the twin study started,” Robinson says. “When the mission was through, spaceflight affected Scott’s gene expression, vision and immune system. It even changed his gut microbiome. Now, we are planning to fly more crew members for long durations, to prepare for future missions to Mars.”

Gaining knowledge like this is invaluable, she says, as “it gives us knowledge we wouldn’t have learned on Earth and we can bring it back and make our lives better here at home.”

Robinson cites an earlier example from the Apollo missions.

“An amazing impact of the miniaturization of thermal control is that it led to the development of neonatal incubators,” Robinson says. “Given the people around the world who are alive today because of these incubators, it may have been one of the greatest achievements of the Apollo era in its return of benefits to humanity.”

It takes time, she says, “but we have similar benefits to humanity coming from research on the ISS.”

Balancing life as a NASA scientist, a wife and a mother has been a challenge for Robinson, but she’s adamant it’s not insurmountable.

“That’s something I try to get across as I mentor young women and men,” she says. “It’s okay to ask for help. Parents need help. I was very fortunate that I had a lot of assistance from my husband, nannies and mother in raising my daughter.”

Finding good child care, she says, is often a huge barrier to people in the workplace – especially moms.

“I let people know they don’t have to shoulder this responsibility on their own,” Robinson says. “I recommend exploring all avenues and using a variety of solutions to achieve balance.”

And what sorts of hobbies does Robinson pursue, when she’s away from the workplace?

“Singing and crafts,” she says with enthusiasm. “I’m a crafty person, who loves fiber arts and visual arts. I enjoy drawing and painting.” And, occasionally, she performs.

“I sing jazz and classical music. I’m working on the repertoire of mezzo arias,” Robinson says. “As Joe and Karen Morse taught me, the arts are as important as the sciences.”

Would Robinson ever like to visit the ISS?

“Oh, yes, absolutely, I’d love to magically be on the station,” she says. “But as I am so prone to motion sickness, I might need a lot of extra encouragement for the journey.”

By Mary-Ann Muffoletto